In 1904 the Louisiana Purchase Exposition transformed St. Louis into a visual encyclopedia. Also known as the St. Louis World’s Fair, this seven-month spectacle drew at least 19 million visitors to the city and thousands of objects from around the world. Similar to previous international expositions, the intentions of the fair’s organizers were to promote their city on a global stage and celebrate American modernity through objects that demonstrated technological, commercial, scientific, and aesthetic innovation. One defining feature set this exposition apart from its predecessors: no previous world’s fair had brought together so many people from so many different cultures and countries. These two aspects jointly shaped the fair’s selection of works of art and their contexts for display across its grounds.

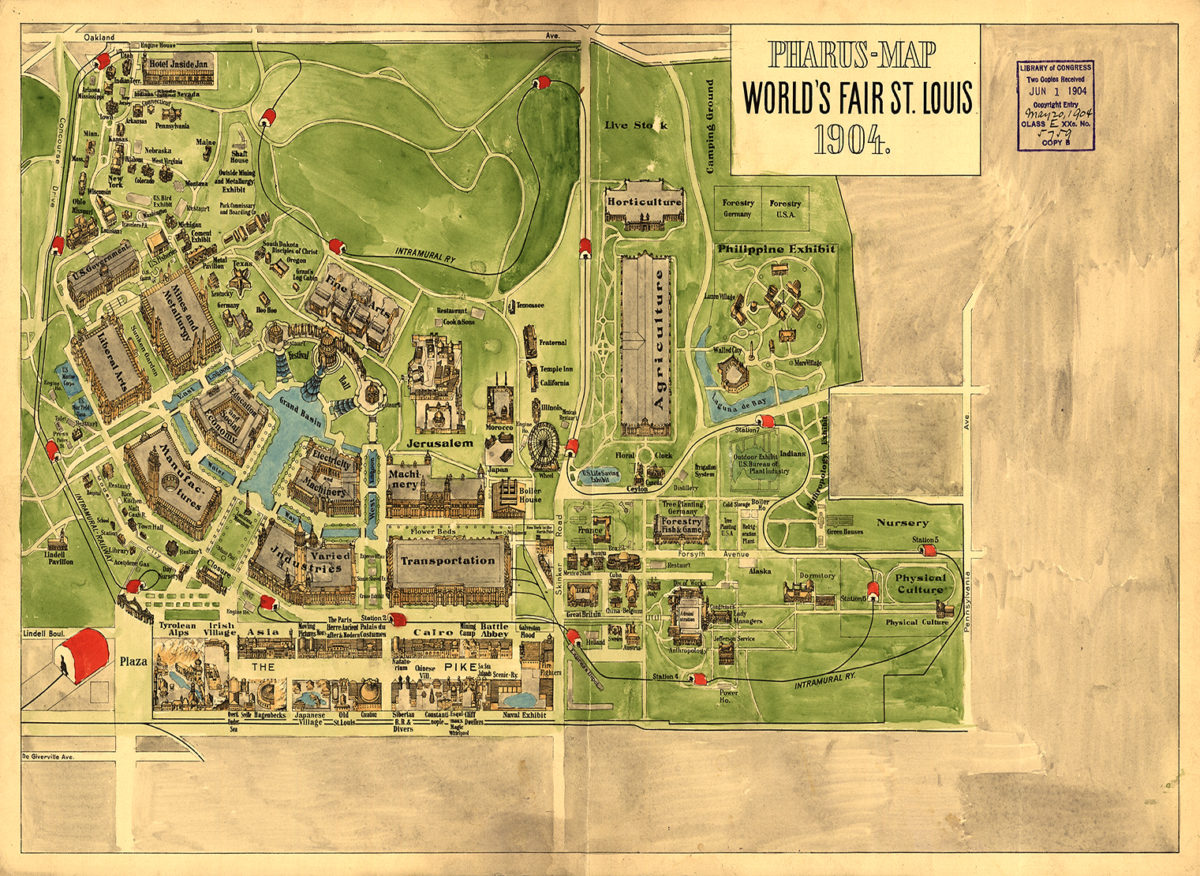

Larger than any prior international exposition, the fair covered 1,200 acres of the western corner of Forest Park with 1,500 buildings constructed mostly from staff, an impermanent material made from plaster and fiber. Only two buildings were intended to outlast the fair: the Flight Cage (now part of the St. Louis Zoo) and the Palace of Fine Arts (now the Saint Louis Art Museum). When Halsey Cooley Ives, the director of the St. Louis Museum of Fine Arts, was appointed to lead the fair’s art department, he advocated for the exposition to build a permanent structure that would become a new home for the Museum. Ives oversaw the organization of approximately 11,000 works of art by nearly 1,500 professional artists from 26 countries for the exhibition.

The 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair both reinforced and dismantled cultural and artistic hierarchies in its displays. Colonializing ideologies underpinned how diverse cultures were exhibited. For example, the Philippine reservation, the fair’s largest section, was designed to introduce Americans to the Philippines, acquired as a colony by the United States in 1898 after the Spanish–American War. Far from a celebration of Filipino cultures, the reservation attempted to present Filipino peoples as “uncivilized” to justify the extraction of profits from their islands’ rich natural resources by the United States.

Yet some fair displays dismantled established hierarchies of artistic media and challenged Eurocentric cultural prejudices. For the first time, a world’s fair included the decorative arts and Native American arts in its official fine arts display. Halsey Cooley Ives believed that “all artwork in which the artist-producer has worked with conviction and knowledge is recognized as equally deserving of respect.”

Compare

Selected Works of Art Related to the 1904 World's Fair

The world’s fair included a variety of artworks from artists around the world, ranging from Winslow Homer’s landscapes to Japanese ceramics and paintings, and works by Native American and Filipino artists. For the first time at any international exposition, decorative objects such as furniture, textiles, and pottery were exhibited as fine art. Ives was appointed to lead the fair’s art museum. He advocated for the Palace of Fine Arts to be the home for the Saint Louis Art Museum and removed the line between fine arts and other forms of artistic workmanship (such as crafts). For instance, under Ives’s new framework, objects made by Native American artists—most of them women—were exhibited for the first time in the fine arts display at a world’s fair.

Looking Prompts

- Imagine sitting in the location of this sea painting.

- What would the air feel like?

- What sounds would you hear?

- What would you smell?

- What activities would you engage in if you were in this place?

- If you could insert one thing into this landscape, what would it be and why? Sketch an image of your addition to this landscape.

-

About this Artwork

Powerful Atlantic waves pound against the rocks on the rugged Maine coast. The water’s surface seems to flicker with the effects of the sunlight that is just beginning to break through the clouds after a storm. For the last 25 years of his life, Winslow Homer observed the moods of the sea and translated them into profoundly dramatic compositions.

Homer proclaimed this work “the best picture of the sea that I have painted.” The fair’s jury agreed and awarded the artist a gold medal. Collector William K. Bixby then purchased the painting from the fair and hung it in his St. Louis home.

Looking Prompts

Look closely at this work of art. Let your eyes wander up and down and side to side.

- Select one of the words below that you feel connects to the artwork, or choose your own word.

shiny joyful dreamy complex detailed textured stiff soft whimsical

fun heavy loud wild peaceful solemn story bold imaginary

musical rhythmic quiet lonely warm cold mellow lively vivid

colorful abstract realistic slick rough mysterious care happy

labor curious memory fuzzy home coarse smooth patterns

- What do you see that inspired your word?

- Write a poem inspired by the painting and the word you chose.

- As you look at this painting, what do you imagine will happen next? Write a very short story or draw a picture to describe what will happen.

Looking extension for teachers

Using the PowerPoint at the bottom of the Art on Display page, show the words listed above with the image and invite students to participate in the activity collectively. Invite students to share their words and poems with the class.

-

About this Artwork

A female mallard perches at water’s edge beside blossoming rose mallow and lush river reeds. This fine example of bird and flower painting (kachō-ga) was exhibited at the fair alongside Japanese ceramics, metalwork, lacquerware, and textiles. For only the second time at a world’s fair, Japanese art was included in the fine arts section and displayed in a pavilion near the Palace of Fine Arts.

Looking Prompts

- After looking closely at this basket, what questions would you ask of the artist who made it?

- Imagine you were an ant eagerly exploring this object. What would the materials feel like under your feet? What sounds would you hear as you explored? What else would you discover?

- Imagine being able to peek inside the basket. What do you imagine it looks like on the inside?

- This basket is about the size of a school backpack. If it were your basket, what is something you would put inside? Write a list of items you might keep in this basket or sketch the items you would include.

-

About this Artwork

The fair featured displays of Native American art across multiple commercial, governmental, ethnographic, and fine art venues. Some venues validated and celebrated artworks by Indigenous makers. A Chitimacha artist used an intricate double-weave technique to create the complex pattern on the lidded basket. It was displayed in the Louisiana State Pavilion as an educational example of the state’s Indigenous craft traditions. Wealthy philanthropists Mary Bradford and Sara McIlhenny, however, organized the basket display to advocate for federal recognition of the Chitimacha tribe. Other baskets were classified as works of art and installed in the Palace of Fine Arts alongside paintings and sculptures created in European artistic styles.

Other displays of Native American art at the fair dismissed or belittled these artistic traditions. For example, the model Indian school showed federal boarding schools that sought to assimilate Native American children through a program of cultural genocide. Students were punished for speaking their Native languages and forced to cut their long hair and wear only Anglo-American clothing. To demonstrate the changes forced on students from the model school, fair organizers invited nonassimilated members of Native American nations to live on the fairgrounds. This group included Native American artists who worked in historic artistic forms, such as San Ildefonso Pueblo potters Maria and Julian Martinez and Pomo weavers Mary and William Benson. While organizers intended their artworks to compare unfavorably with those produced by students at the model school, the opposite proved true—buyers purchased their ceramics and weavings in great numbers. Paradoxically, the racist program of attempted assimilation helped to assemble the largest collection of Native art in an international exposition to date.

Looking Prompts

Set a timer for 60 seconds. Look closely at these two images for one minute.

- What do you notice?

- Zoom in on the images using the zoom function. As you look even closer, what more do you discover?

- What do you wonder about the materials or the process for making these objects?

- The artists who created these artworks incorporated intricate patterns and weaving techniques. Think about fabric or cloth that you have or wear. What types of patterns do they have? If you could create your own pattern for a cloth, what would you include? Draw your pattern.

Looking Prompts

- When looking at these objects, what stands out to you most?

- Compare and contrast these two baskets. Describe what is similar about them. Then describe what is different.

- What would you like to learn about these baskets?

-

About these Artworks

Delicate embroidery embellishes the shimmering surface of the cloth, made from pineapple fibers native to the Philippines. Filipino artists and craftspeople also used other native plants—rattan and nito (climbing fern), in particular—to weave objects such as baskets with eye-catching patterns and richly textured backpacks.

Similar to the fair’s exhibition of works by Indigenous American artists, display contexts and contradictions shaped viewers’ responses to objects by Filipino artists. The fair’s largest exhibition was the Philippine reservation, a 47-acre site intended to introduce Americans to the territory that had become a US colony six years earlier following the Spanish–American War. Works of art in a variety of contexts could be found throughout the 130 buildings of the attraction. The Manila Building housed the Department of Manufactures exhibit, which included examples of handwoven fabrics and embroidery made from native pineapple and banana fibers. The reservation’s most popular attraction was five re-created villages, each devoted to a specific ethnic group, where more than 1,100 Filipinos resided and performed as living exhibits for the entertainment of visitors. Members of the Visayan, celebrated for their expertise in weaving, woodcarving, and fiber braiding, gave regular demonstrations of their skills, and sold the results, earning the highest revenue of the five villages.

The reservation also included an art gallery in the Philippines Government Building that exhibited 90 sculptures and paintings produced in European academic styles, including Juan Luna’s monumental, grand prize–winning Spoliarium. This situation demonstrates the double-edged sword of colonializing perspectives: organizers restricted the reservation’s fine art gallery to objects made by Filipino artists working in European-derived styles of painting and sculpture, while equally accomplished Filipino Indigenous forms, such as the textiles and basketry in this section, were categorized as commercial products and displayed in the Department of Manufactures exhibit. This segregation of exhibition venue by object type reinforced colonializing judgments that defined Indigenous works as less advanced artistic expressions.

Though this hierarchy has shifted today, cross-cultural dialogues are still more commonly perceived as occurring in one direction—the study and travel of Westerners to the Philippines. However, less widely recognized is the engagement of Filipino artists in cultural dialogues that spanned multiple directions, such as the travels of Juan Luna, who studied in Madrid and lived for extended periods in Paris.

Detail view of Block Out the Sun

Looking Prompts

- Select either the full view of the artwork or the detail image to explore in depth. Write a caption for the image you chose to view that describes what is going on and what message you find in this work of art.

- What do you see that supports your caption?

-

About this Artwork

In 2019 Filipino American artist Stephanie Syjuco photographed her hands as they obscured faces of Filipinos in images taken at the fair in 1904. Organizers had brought more than 1,100 Filipinos to St. Louis to perform as living exhibits in re-created villages on the Philippine reservation. The reservation’s overarching goal was to persuade the American public that Filipinos were “savage” and “uncivilized.” This characterization could be used to justify their colonization by the United States, which then could reap profit from the islands’ extremely rich natural resources with impunity. Professional and amateur photographers took many images of these villages. Such images transform their subjects into unwilling actors in disempowering and long-lasting historical, political, and social narratives.

Block Out the Sun disrupts these narratives when the artist photographed her hands covering the faces of people on the Philippine reservation, thereby blocking the viewer’s ability to scrutinize these individuals. Syjuco’s hands challenge the power of the anthropological gaze, which seeks to define its subjects through reductive visual judgments. By “literally block[ing] out the viewer’s ability to absorb or own these images,” she seeks to reclaim the privacy of the Filipino subjects.

As the world’s fair demonstrated, meanings of objects can be manipulated by the ideologies that underpin their displays. Additionally, access to the displays discussed here was restricted in varying degrees by gender, class, and race. And yet, while these frameworks are limiting, objects nonetheless have the capacity to speak beyond historical agendas and inequitable environments, as Block Out the Sun so powerfully demonstrates.

- Listen to learn more

Additional Resources

-

Image Credits

Image Credits in Order of Appearance

Winslow Homer, American, 1836–1910; Early Morning after a Storm at Sea, 1900–1903; oil on canvas; 30 1/4 x 50 inches; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of J. H. Wade 2021.182

Komuro Suiun, Japanese, 1874–1945; Summer Scene with Solitary Duck amidst Rose Mallow and River Reeds, 1903 or 1904; hanging scroll; ink, color, and oystershell white pigment (gofun) on silk; image: 44 1/2 x 27 1/2 inches, scroll: 81 x 34 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, The Langenberg Endowment Fund 101:2017

Chitimacha artist, Louisiana; Basket with Lid, c.1900; river cane and dye; 14 3/8 x 14 3/16 x 14 3/16 inches; Loaned by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, Purchased from Miss McIlhenny, 1906 2021.175

Filipino artist, Philippines; Man’s Backpack, before 1904; rattan and peel; 20 5/8 x 12 x 9 5/8 inches; Loaned by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, Gift of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum (also known as the Philadelphia Civic Center Museum), 2003 2021.181

Visayan artist, Philippines; Cloth, late 19th century; pineapple fiber, silk, and cotton; 14 3/4 x 74 7/16 inches; Loaned by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, Gift of Philadelphia University, 2016 2021.176

Pala’wan artist, Philippines; Baskets, before 1904; rattan and nito; left basket: 9 x 10 5/8 x 8 7/8 inches, right basket: 9 11/16 x 11 1/8 x 11 inches; Loaned by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, Gift of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum (also known as the Philadelphia Civic Center Museum), 2003 2021.179-.180

Stephanie Syjuco, American (born Philippines), born 1974; Block Out the Sun, 2019; pigment prints mounted on aluminum; approximate case dimensions: 36 x 84 x 48 inches, image (individual prints): 8 x 10 inches; Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York 2021.185.1-.30; © Stephanie Syjuco