Installation view of Art Along the Rivers: A Bicentennial Celebration

This audio guide features 15 commentaries on objects created over the past 1,000 years near the confluence of some of the continent’s most powerful rivers—the Mississippi and Missouri. Listen to a general introduction, narrators from the Saint Louis Art Museum, and voices from the confluence region community.

-

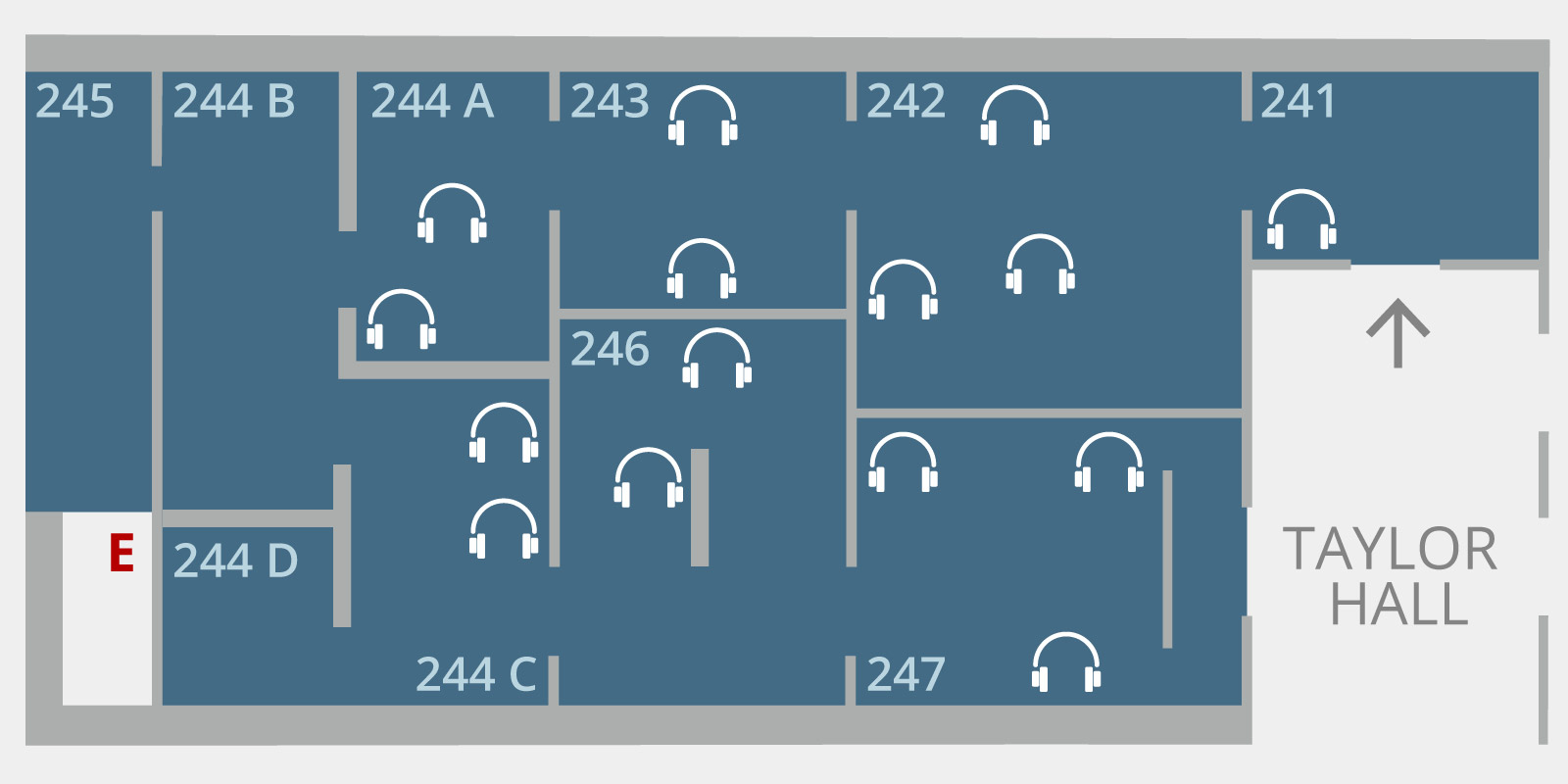

Access and Assistance

Free Public Wi-Fi

The Saint Louis Art Museum offers free Wi-Fi to visitors. From your device, access the SLAM_GUEST network.

Large Print Labels

Large-print labels are available on your own device and upon request at the Taylor Hall Welcome Desk.

AUDIO GUIDE TRANSCRIPT

The audio guide transcript is available to view on your own device.

Race Wall, St. Louis, Missouri, 1971, printed 1999

Ken Light, American

- Transcript

Speaker: Abdul-Kaba Abdullah

Executive Director

Park Central DevelopmentHi, my name is Abdul-Kaba Abdullah. I’m from St. Louis, Missouri, executive director of Park Central Development, which is a community development corporation in St. Louis that builds urban, vibrant, equitable neighborhoods for all people to live, work, and play. We actually have done probably 75 percent of the murals in the neighborhood called the Grove. And when this mural was curated in 1968, it was done at a time where we were really trying to, as Black people—or at the time, Negroes—were trying to have a dignity of respect. This place was set right outside of Pruitt-Igoe, this mural. Automatically, the first thing I think about is the picture of my great-grandmother that we have, who lived in the Pruitt-Igoe, and I think about just the stories that they would tell about really the conditions. But through it all, I think it shows the greatness and the resiliency of the African American people but really Black people and people of the diaspora of Africa.

As I sit here and I look towards the future, and I look at the two older gentlemen in the picture, the first thing I see is not despair but a tiredness. But I see wisdom, and I see them looking, actually, I see them looking at me to say, “Hey, it’s your time to take this baton and these paintbrushes and put this mural back in place.” Not only what’s existing, but because as I look at it, they’re all gone. They’ve all left this earth, but their mantles are here. So, either you pick those mantles up or you help to pass it to who that mantel is prepared for. I see, “Your turn, youngblood.” That’s what I see. You know, that’s how the old-timers say it. So that’s what I see.

A lot of the murals we’re working on now are important, but it’s the people who are doing the murals and making sure that there is space for any Black and brown artist because, believe it or not, even in these spaces, they have not been traditionally allowed to exist or allowed the opportunity. And when they do, they’re often underfunded or not funded to the same level. So even in access, you still see it in the arts. So, a big part of the murals that I’m working on is access for people and access for artists. And if I was asked to re-create this, what would it look like? I think this is actually the perfect mix of people for the period. This is what Black America has been able to rise up through, and through these figures and through the culture that we’ve been able to create. I think it’s important to anchor this mural because this mural becomes the shoulders, as we say, we always stand on the shoulders of giants. The thing that I would want visitors to know and to realize is that Black is beautiful. Black is powerful. Black is love. Black is accepting. And Black is dignity.

- Gallery Text

Ken Light, American, born 1951

Race Wall, St. Louis, Missouri, 1971, printed 1999

gelatin silver printSaint Louis Art Museum, Gift of August A. Busch Jr., by exchange 39:2021

Two men sit among painted portraits of Black leaders. This photograph documents one of St. Louis’ most important community-based art projects: a three-story mural created in 1968 by volunteers from local civil rights groups. This “Wall of Respect” was part of a national urban mural movement celebrating African American achievement.

A hub for Black activism, concerts, and rallies, the mural also became a target for vandalism, such as the white paint that partially defaces several portraits. Despite these acts, the mural held a central place in its community for over a decade, before its building was demolished in the 1980s.

Learn More

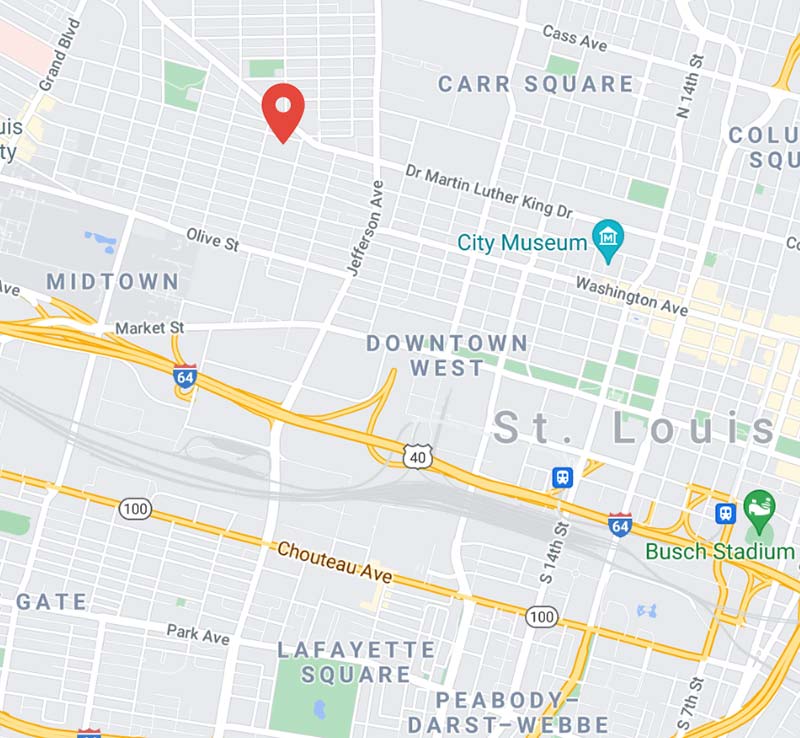

Detail map of the former location of Leroy White’s Wall of Respect mural on Franklin Avenue, St. Louis (red marker).

Credits

Ken Light, American, born 1951; Race Wall, St. Louis, Missouri, 1971, printed 1999; gelatin silver print; image: 12 1/2 x 18 3/4 inches, sheet: 16 x 20 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of August A. Busch Jr., by exchange 39:2021; © Ken Light

Map data © 2021 Google