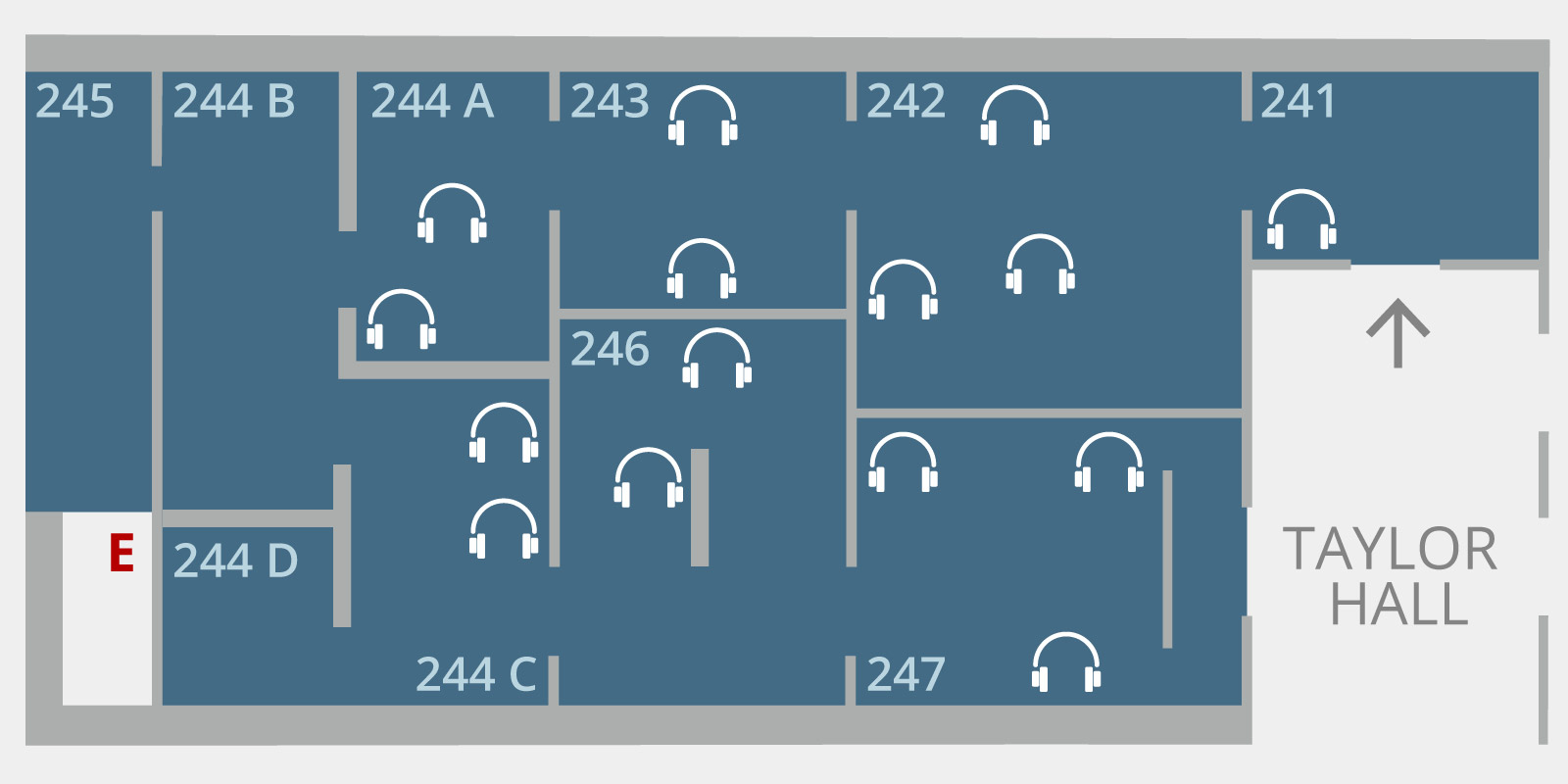

Installation view of Art Along the Rivers: A Bicentennial Celebration

This audio guide features 15 commentaries on objects created over the past 1,000 years near the confluence of some of the continent’s most powerful rivers—the Mississippi and Missouri. Listen to a general introduction, narrators from the Saint Louis Art Museum, and voices from the confluence region community.

-

Access and Assistance

Free Public Wi-Fi

The Saint Louis Art Museum offers free Wi-Fi to visitors. From your device, access the SLAM_GUEST network.

Large Print Labels

Large-print labels are available on your own device and upon request at the Taylor Hall Welcome Desk.

AUDIO GUIDE TRANSCRIPT

The audio guide transcript is available to view on your own device.

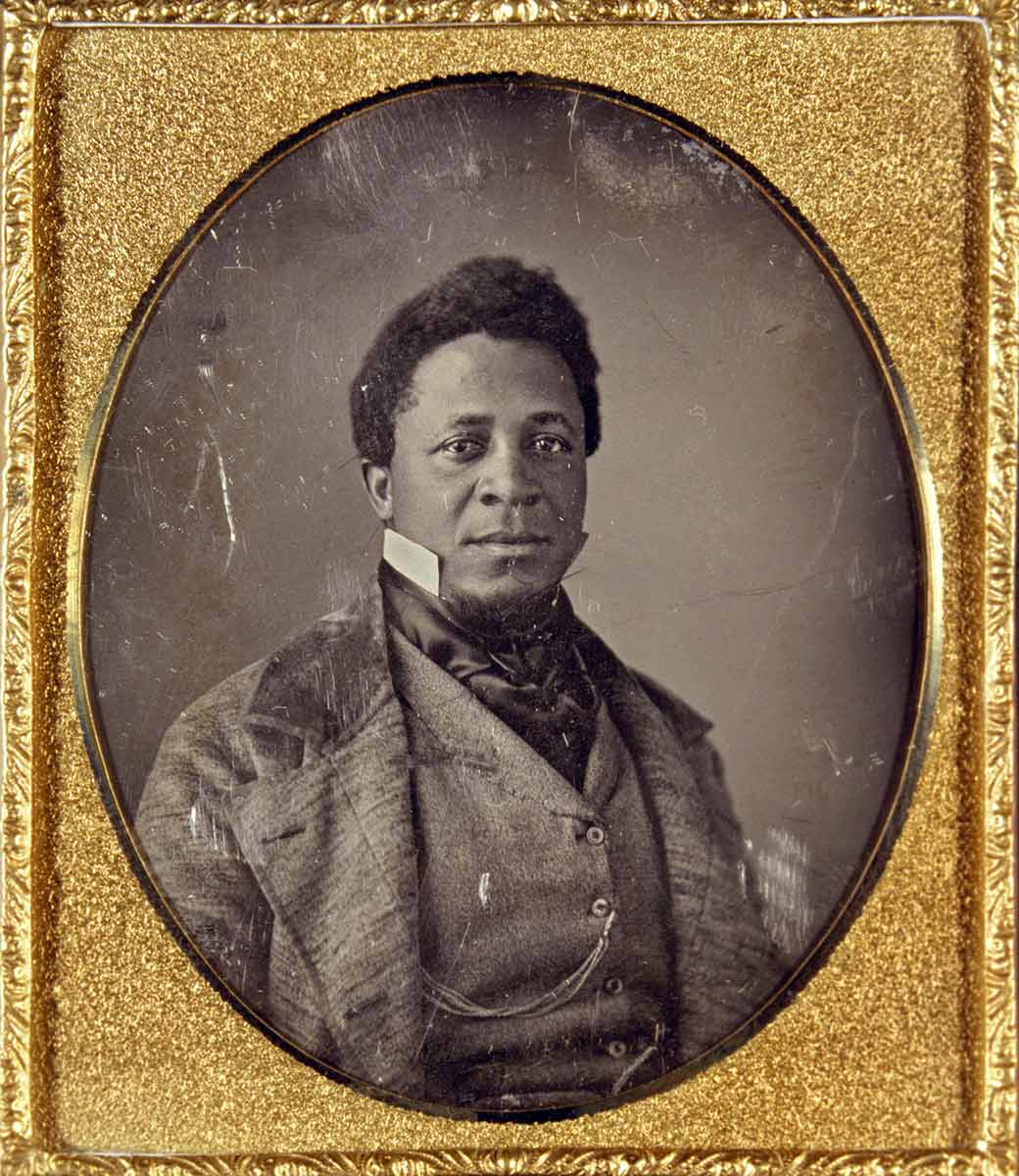

Robert J. Wilkinson, Barber of the Southern Hotel, c.1860

Thomas Martin Easterly, American

- Transcript

Speaker: Lois Conley

Founder and Executive Director

The Griot Museum of Black HistoryThe following audio recording acknowledges physical and sexual violence against Black people.

Hello, I am Lois Conley, founder and executive director of the Griot Museum of Black History, thanking you for stopping by to learn a little about the state of Black life in the antebellum St. Louis where Robert J. Wilkinson lived.

When Robert J. Wilkinson moved from Cincinnati to St. Louis in the 1840s, he was among some 1,400 free people of color living in antebellum St. Louis. But life was a complicated dichotomy for Black people. They were forbidden to gather for meetings, including church meetings, unless in the presence of a white person. It was illegal to teach Black people—enslaved or free—to read and write. Despite their status, all Black people were required to have a pass or be arrested. They had the right to seek legal advice but could not testify against a white person. Enslaved Black people in antebellum St. Louis could not legally marry. None could vote. Blacks were allowed a trial by jury, but a jury only of all white men. Physical abuse, of torture, of an enslaved person was a crime, but the rape of an enslaved woman or girl was not.

Just a few years before Wilkinson’s arrival, Francis Mackintosh, a free Black man, had been lynched by a violent St. Louis mob. Some enslaved Blacks were allowed to work outside of the owner’s household, often earning enough money to purchase their own freedom and that of family and other enslaved persons. However, any free Black person, born free or manumitted, who had migrated to St. Louis after 1847 had to be gone by 1860 or risk being enslaved. Like his father and brother, Robert J. Wilkinson, the subject of this Thomas Easterly daguerreotype, was a skilled barber. He owned and operated a thriving barbershop in a popular downtown hotel that was frequented by statesmen, businessmen, and other white movers and shakers. Yet because of discriminatory public accommodation laws that prevailed, he could work there, he could even own a business there, but he could not rent a room and spend the night there.

- Gallery Text

Portraiture

The idea of a portraitist at work, standing behind a canvas or camera to create an image of their subject, might seem entirely unrelated to an industrialized assembly line. But portraiture can also be considered an industry because its producers create a closely related set of goods.

In the 17th century, colonists brought European conventions of portraiture with them to North America, where they took root. As Missouri towns expanded during the 19th century, so too did the portraiture industry. Artists traveled to the region to meet the population’s growing demand for images of themselves that would demonstrate their social, economic, and familial ambitions.

By the 1840s, photography began to expand portraiture’s conventions and expectations. Today, contemporary artists continue to challenge the fundamentals of portraiture: who is portrayed, why, and how.

Thomas Martin Easterly, American, 1809–1882

Robert J. Wilkinson, Barber of the Southern Hotel, c.1860

daguerreotypeKeokuk, or the Watchful Fox, 1847

hand-colored daguerreotypeUnidentified Mother and Small Son, c.1850

hand-colored daguerreotypeThomas Forsyth, Mountain Spy and Guide, 1847

daguerreotypeCourtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis 2021.54–56

Thomas Martin Easterly created a collective portrait of the confluence region through his daguerreotypes. In this early type of photography, artists captured one-of-a-kind images on silver-coated copper plates. Easterly’s camera recorded the candid expressions of hundreds of St. Louis residents and visitors, such as a little boy’s scowl or a man’s furrowed brow. His psychologically penetrating portrait of the Sauk and Fox leader Keokuk is considered the first photographic portrait of a Native American.

Easterly also photographed the area’s African American residents, such as Robert J. Wilkinson. Many may have agreed with American abolitionist Frederick Douglass that the “democratic art” of photography allowed African Americans to appear as individuals rather than as reductive stereotypes. Faster to make and less expensive to purchase than paintings, daguerreotypes changed expectations for and access to portraiture.

Learn More

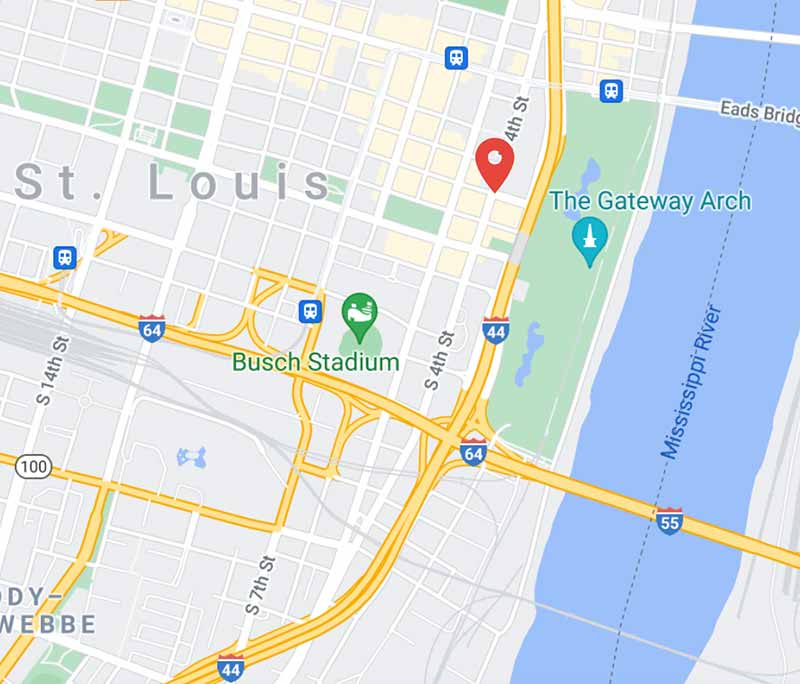

Detail map of the site of Robert J. Wilkinson’s business at 4th and Pine Street, St. Louis (red marker).

Credits

Thomas M. Easterly, American, 1809–1882; Robert J. Wilkinson, Barber of the Southern Hotel, c.1860; daguerreotype; 4 x 3 1/2 inches; Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis 2021.56

Map data © 2021 Google