Yoruba artist; Wrapper (detail), mid- to late 20th century; cotton, rayon; 75 x 53 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of Thomas Alexander and Laura Rogers 190:2011

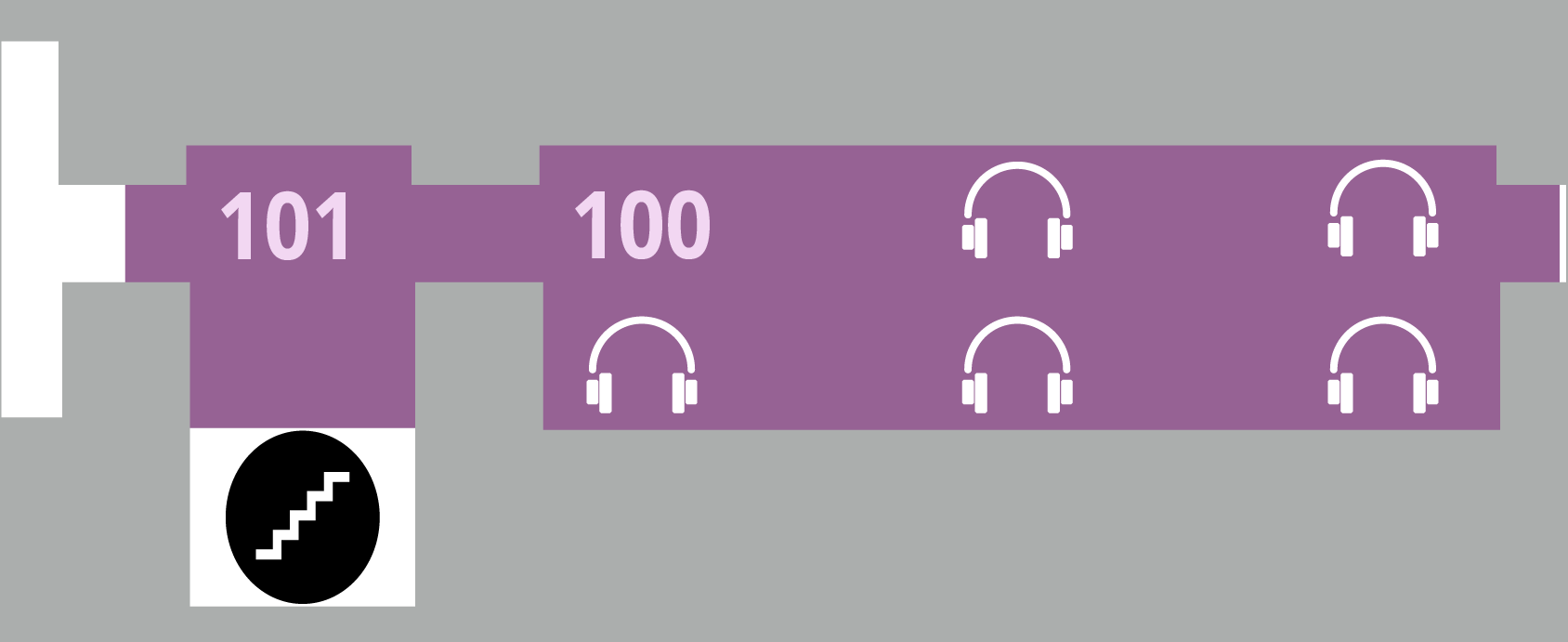

The exhibition audio guide highlights personal connection and knowledge of textiles created by Yoruba weavers in southwestern Nigeria for celebratory and ceremonial occasions from the early 19th to late 20th century.

-

Access and Assistance

Free Public Wi-Fi

The Saint Louis Art Museum offers free Wi-Fi to visitors. From your device, access the SLAM_GUEST network.

Large Print Labels

Large-print labels are available on your own device and upon request at the Taylor Hall Welcome Desk.

AUDIO GUIDE TRANSCRIPT

The audio guide transcript is available to view on your own device.

-

Videos and Images

Learn more about aso oke textiles from images and videos prepared by Tony Agbapuonwu.

Man's Robe (agbada), early 20th century

Yoruba artist

- Transcript

Speaker

Benjamin Olayinka Akande

Board Member

Saint Louis Art MuseumHello, I’m Benjamin Olayinka Akande, born in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria, raised in Ogbomosho and Ibadan and Lagos. And I am a long-standing board member of the Saint Louis Art Museum.

What is important in the Yoruba tradition are respect, honor, and formality. When you see people that are wearing the agbada, and it is made from aso oke, that is the holy grail of all agbadas—the ones that are made from aso oke. We say this was the original three-piece. So, you’ve got the three-piece suit—the original three-piece is the agbada.

I grew up being taught and being exposed to the regality and the importance and the tradition of agbada. And when they wear it, it seems to give them more power, more, more confidence, as they walk around in their agbada. And initially, you wear the agbada with your hands spread out, so that you can fully feel the effect. And then as you, as you get even more comfortable, you then bring the agbada—fold it up on the left, fold it up on the right. And when you do that, it actually shows the second piece, which is the internal, sort of like, second piece of the outfit itself. And essentially, for us, it speaks to the tradition, the heritage, of being a Yoruba man.

I remember my first experience with aso oke agbada was wearing it to a naming ceremony. Naming ceremonies are as important as the birth of the child itself. My dad took me to that occasion, and I got a chance to wear my first aso oke agbada to that event. And I was a little boy; I was like 10 years old. The other occasion is, it’s also worn at weddings. But then before the weddings, the engagement is also a critical juncture where the aso oke is worn. Also, I remember three years ago when I went to bury my dad, I had a special aso oke sewn for me. And we chose my father’s favorite color, which was purple. And three weeks ago I was in Nigeria for the funeral of my in-law. When they brought his remains into the house for him to lie in state overnight into the morning, he was dressed in his favorite aso oke agbada, similar to the brown one here.

I end with that because agbada is there to celebrate your birth; aso oke agbada is there to celebrate your passing. It is a cyclical experience that starts from birth until the very end.

- Gallery Text

“[The] one who wears expensive aso oke to pose resplendent in wisdom…”

– Oriki (oral praise poem) dedicated to Bamigboye (c. 1885-1975), a Yoruba sculptorThe Aso Oke Triad and Agbadas (Men’s Robes)

These men’s robes, called agbadas, introduce the three historical elements of aso oke that have continued to inform production of this cloth to the present day. Sanyan is tan wild silk. Alaari is magenta imported silk. Etu is indigo cotton. Synthetic fibers and pigments largely replaced the archetypal ones in the early 20th century. Many of these later cloths may still be referred to as sanyan if beige, alaari if purple, or etu if blue.

The agbadas reflect the mastery of Yoruba weavers, embroiderers, and tailors. The voluminous form and elaborate embroidered designs of these robes originated in the Islamic regions of northern Nigeria. Tailors reinterpreted the form for local clientele by utilizing aso oke, rather than imported cloth. Embroiderers reimagined the stitched embellishments, adapting designs that Koranic calligraphy experts developed in the north.

These agbadas share motifs including “king’s drum,” a circle on the right chest symbolizing chieftancy, and multiple “knives,” elongated triangles associated with wealth. The embroidery, combined with the splendor of the aso oke itself, lends extra elegance to these immense robes that amplified the physical presence of an elite Yoruba man.

Yoruba artists

Man’s Robe, early to mid-20th century

CottonGift of A. Patrick Irue and Amber Wamhoff, in memory of Dr. Leonard and Mrs. Lenora Gulbransen 180:2015

Etu

The deep indigo hue of this agbada creates an intensely dramatic contrast between the aso oke cloth and the embroidered designs. Upon close inspection, the cloth reveals a delicate checked pattern alternating light- and dark-blue threads. Called etu in Yoruba, this subtle tonal effect is named for its similarity to the speckled feathers of a guinea fowl (Numida meleagris). The saturation of etu cloth corresponds to the length of time its threads were submerged in indigo dye, ranging from light (ofeefe) to medium (ayinrin) and dark (dudu). In Yoruba aesthetics, dudu signifies coolness, composure, and self-control, associating these qualities of an effective leader with the elite man who wore this robe.Yoruba artists

Man’s Robe (agbada), early 20th century

silk (sanyan), cottonFriends Fund 11:2023

Sanyan

This agbada suggests great presence despite a subtle, monochromatic palette comprised of light-brown silk fibers, narrow white cotton warp stripes, and ivory embroidered designs across the chest and back. Called sanyan, the undyed silk reflects the naturally occurring color of the silk-moth (Anaphe infracta or Anaphe moloneyi) cocoons from which the threads were sourced (see image). The silk-making process involves harvesting the cocoon pods from certain trees, then boiling them to separate the outer shell from the soft, fibrous interior. Artisans then spin the fibers by hand into textural threads that weavers transform into cloth. This light-colored garment suggests the radiance of funfun. Funfun signifies purity and wisdom in Yoruba color theory and is associated with Obatala, the Yoruba deity (orisha) who sculpted humans into being and is considered “lord of white cloth.”Yoruba artists

Man’s Robe (agbada), late 19th century

silk (alaari), cottonFunds given in memory of Pauline E. Ashton 12:2023

Alaari

Lively embroidered designs and varied wide, narrow, and pin-stripes, comprised of magenta silk and white-and-black cotton, combine to create this dramatic agbada. Called alaari, the bright purple silk fibers began arriving in Nigeria by the 18th century via trans-Saharan trade. These fibers were “waste silk,” remnants from textile production in Europe and northern Africa, which were dyed purple and then traded into western Africa. In Nigeria, spinners transformed these fibers into alaari threads. The distinctive color imbues this robe, and the man who wore it, with the powerful associations of pupa. In Yoruba aesthetics, pupa connotes warm and hot temperatures, while funfun (white) and dudu (black) suggest coolness. This agbada’s interplay between the dominant alaari threads and complementary funfun and dudu stripes suggests the balanced demeanor essential to any male leader.

Learn More

Photograph of Dr. Benjamin Ola. Akande and family

Photograph of Dr. Benjamin Ola. Akande and family

Man's Robe (agbada)

Credits

Yoruba artist, Man's Robe (agbada), early 20th century; silk (sanyan) and cotton; 53 x 117 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Friends Fund 11:2023

Courtesy of Dr. Benajamin Ola. Akande

Yoruba artist, Man's Robe (agbada), late 19th century; silk (alaari) and cotton; 49 x 92 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Funds given in memory of Pauline E. Ashton 12:2023