designed by Giuseppe Figoni, French (born Italy), 1894–1978; made by Delahaye, Paris, active 1894–1954; leather interior by Hermès, French, founded 1837; Type 135MS Special Roadster, 1937; engine: six-cylinder in-line pushrod engine, two valves per cylinder, 3557 cc, 160 hp at 4200 rpm; wheelbase: 116 inches; Revs Institute, Inc., Naples, Florida; © 2024 Revs Institute, Photo: Peter Harholdt

Hear from a variety of experts about the transformative role of the automobile in pre–World War II France, highlighting innovations across art and industry by those who embraced it as a provocative expression of the modern age.

-

Access and Assistance

Free Public Wi-Fi

The Saint Louis Art Museum offers free Wi-Fi to visitors. From your device, access the SLAM_GUEST network.

Large Print Labels

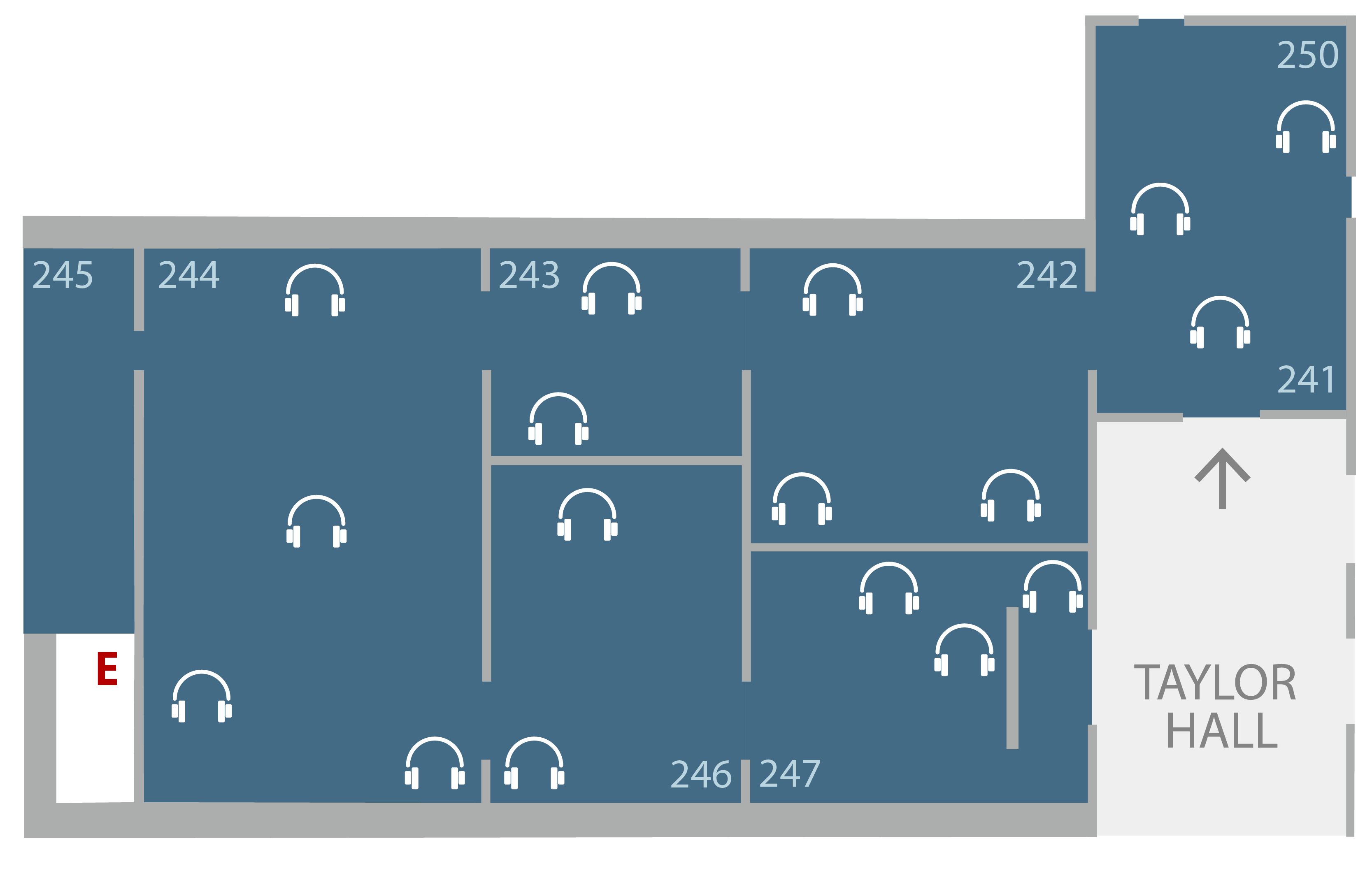

Large-print labels are available on your own device and upon request at the Taylor Hall Welcome Desk.

AUDIO GUIDE TRANSCRIPT

The audio guide transcript is available to view on your own device.

-

Automobile Details

View the Automobile Details page to learn more about the 12 exemplary cars featured in this exhibition.

Evening Coat, 1924

Paul Poiret, French; made by Poiret, Paris, France

- Transcript

Speaker

Sarah Berg

Research Assistant, Decorative Arts and Design

Saint Louis Art MuseumHello, I’m Sarah Berg, research assistant for decorative arts and design at the Saint Louis Art Museum.

Let’s take a look at this draped evening coat with brocade sleeves by the French designer Paul Poiret. Vivid green silk is gathered at the wearer’s side by a neat row of gold-toned buttons, which repeat on the high collar and the cuffs. This subtle swoop of fabric at the midsection accentuates Poiret’s signature uncinched silhouette. Leading to the dawn of the 20th century, fashions favored tightly corseted waists. In response, Poiret promoted straight and roomy styles in dazzling colors and with minimal but experimental tailoring.

Touted as the “King of Fashion,” Poiret was widely credited for this new silhouette, though other couturiers also produced unstructured designs before 1910. This movement to liberate the body in women’s clothing stemmed in part from a craze that was sweeping France: Orientalism. Against a backdrop of French colonial conquests in Africa and Asia, turbans, tunics, robes, and pants came to represent an imagined, exoticized Eastern style. Poiret’s draped, rectilinear garments, including wide coats meant to protect the clothing while driving, were especially inspired by the Japanese kimono and North African abaya.

The coat in front of you belonged to the Polish American cosmetics mogul Helena Rubinstein, who was an avid collector of art and fashion. Her books and lectures on skincare, diet, and beautifying techniques drove sales of Helena Rubenstein–branded lipsticks, powders, and creams and solidified her public image as an early beauty guru. She frequently wore Poiret’s creations and even solicited the designer, who promoted fashion and interior decoration as equal parts of one’s personal expression, to furnish her beauty clinic in Paris.

- Gallery Text

Paul Poiret, French, 1879–1944

made by Poiret, Paris, France, active 1903–1929Evening Coat, 1924

silk charmeuse, silk and metallic-thread brocade, and brass buttonsLoosely draped acid-green silk satin contrasts with the heavy gold brocaded sleeves and collar of this evening coat by Paul Poiret. Unstructured silhouettes realized with sumptuous textiles, bold closures, and vivid colors were trademarks of the groundbreaking Parisian couturier.

This coat was owned by an equally audacious innovator, Polish American cosmetics tycoon and art collector Helena Rubinstein. An icon of the liberated, modern woman, Rubinstein was an avid motorist who famously shunned the veils typically worn by women to protect their skin when driving in open-top automobiles.

Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society 2025.08

Slow Work in Fast Times

A “collaboration of the engineer and the artisan,” French automobiles flourished thanks to advances in science and technology as well as knowledge passed down over generations. During this period, wealthy clients would buy an automobile chassis—which included the engine, wheels, and steering shaft—from a manufacturer. A coachbuilder then designed and created a custom body, which could take as much as 2,000 hours to complete.

Through patronage and partnerships, ideas moved fluidly across design disciplines. Conceived like compact rooms, coachbuilt cars borrowed the same dazzling fabrics, sumptuous materials, and creative paint treatments popular in fashion and interiors. In turn, automobiles exemplified ingenious storage and space planning, new technologies, and flexible mobility.

These reciprocal influences were in full view at the 1925 Paris Exhibition. Temporary pavilions brimmed with shimmering textiles, furniture in precious woods, gem-encrusted couture, and opulent transportation. Contributors embraced avant-garde art movements and reimagined historical craft, simplifying forms, abstracting patterns, and flattening ornamentation. France’s exploitative colonial empire, which spanned parts of Africa and Asia, was a key source of raw materials, technical expertise, and visual inspiration. The exhibition’s French title, Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, and its luxurious blend of modern aesthetics inspired the term Art Deco.

Learn More

Helena Rubinstein in silk ensemble with cape by Poiret, c.1925

Woman's Green Evening Coat, 1924

designed by Paul Poiret; made by Poiret, Paris, France

Credits

designed by Paul Poiret, French, 1879–1944; Woman's Green Evening Coat, 1924; silk; Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society 2025.08

Helena Rubinstein in silk ensemble with cape by Poiret, c.1925; Fashion Institute of Technology, Helena Rubinstein collection, 1953-2011 US.NNFIT.SC.284.1.1.09.017