Attributed to Deborah Goldsmith, American, 1808–1836; Family Portrait (detail), c.1832; oil on panel; 15 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch 24:1981

There’s always more to the story of a painting than what’s hanging on a wall. While we may never know all the details, looking at a painting from a different angle can lead to fascinating discoveries—or in some cases, even more questions. Careful conservation of paintings can unveil writing on the backside, or verso of a work. Some inscriptions are straightforward and predictable, like the artist’s name and the date. Sometimes, the inscription is illegible, insightful, or even cryptic.

With the exception of those who work to uncover the text, the conversation remains largely between the artist and the wall. In an effort to bring curious SLAM visitors into the chat, here is a look into a selection of SLAM collection works with inscriptions.

It’s not uncommon for paintings to include inscriptions regarding the work itself, like the name of the artist or a description of the content. Port-en-Bessin: The Outer Harbor (Low Tide) (1888) by George Seurat, for example, has “Seurat/Port.en.bessin/Marée basse” handwritten by the artist on the verso. The verso of Sandstorm (1947) by Alice Rahon states plainly, in black paint, “Alice Rahon Paalen. Mexico 47 sandstorm.”

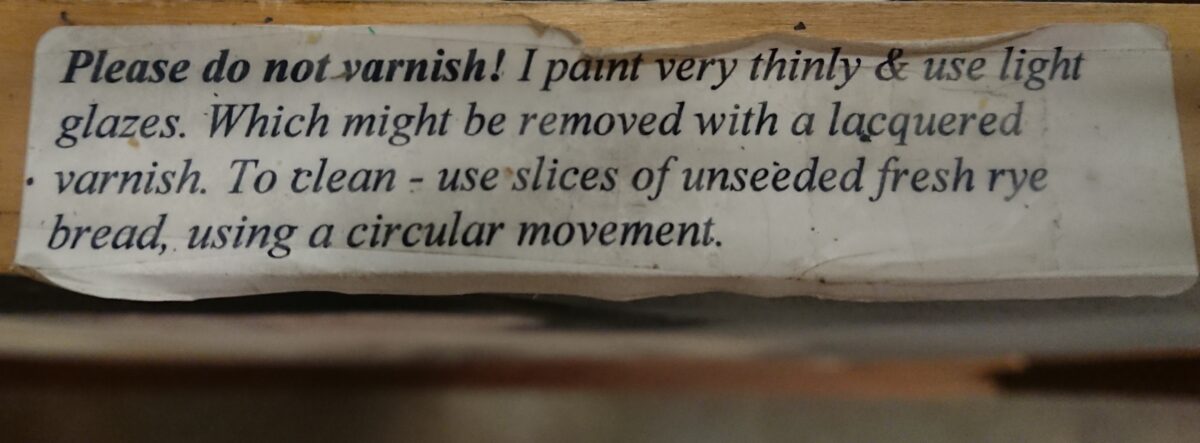

With some paintings, the artists go a step further and give specific instructions for future conservators. Two paintings by Sylvia Sleigh, who was a Welsh painter active in the United States, have an artist label fixed to the back of the canvas frame stating, “Please do not varnish! I paint very thinly & use light glazes. Which might be removed with a lacquered varnish. To clean—use slices of unseeded fresh rye bread, using a circular movement.” As you may imagine, fresh rye bread is not kept anywhere near the art—for this painting, conservators use conservation-grade sponges.

-

Sylvia Sleigh, Welsh (active United States), 1916–2010; Bridget Seated, 1959–60; oil on canvas; 35 x 28 1/2 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift from the Estate of Sylvia Sleigh 693:2018; © Estate of Sylvia Sleigh

-

Sylvia Sleigh, Welsh (active United States), 1916–2010; Kevin Eckstrom, 1980; oil on canvas; diameter: 17 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift from the Estate of Sylvia Sleigh 694:2018; © Estate of Sylvia Sleigh

-

A label on the verso of Sylvia Sleigh's painting, Bridget Seated

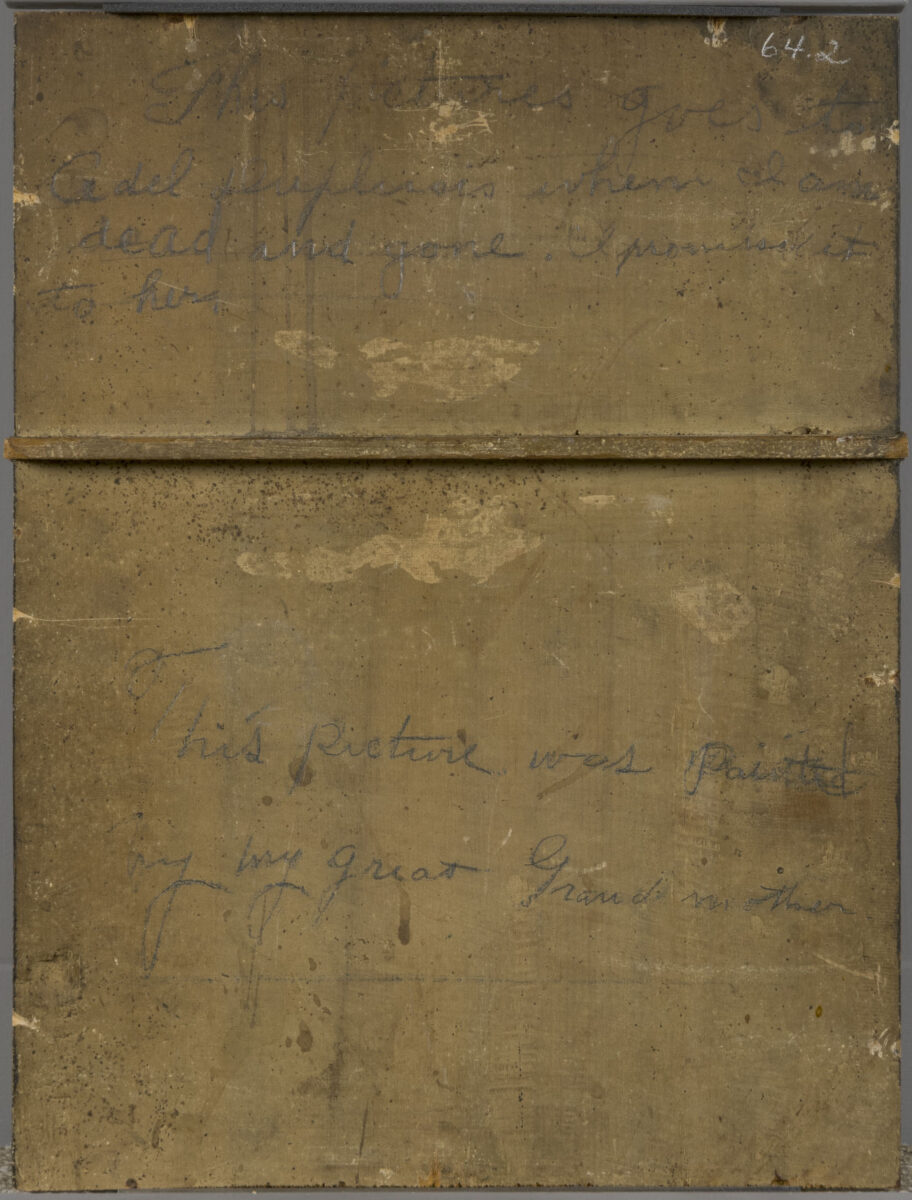

Unfortunately, not all inscriptions are as comprehensible as these. On the backside of Deborah Goldsmith’s Family Portrait (c. 1832), conservators found, “This picture goes to Adel [Duplinois] when I am dead and gone. I promised it to her,” and “This picture was painted by my great Grandmother,” both inscribed by unknown writers. These two passages raise a few big, unanswered questions. First, what is the correct spelling of the name in the first inscription? The cursive writing is difficult to interpret; “Duplinois” is an educated guess, and that person’s relationship to the artist is also unknown. Second, who wrote these passages? The differing script suggests they were written by two different people, and which of the artist’s many great-grandchildren wrote the second inscription?

-

Attributed to Deborah Goldsmith, American, 1808–1836; Family Portrait, c.1832; oil on panel; 15 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch 24:1981

-

Attributed to Deborah Goldsmith, American, 1808–1836; Family Portrait (transcription on the reverse support), c.1832; oil on panel; 15 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch 24:1981

In other cases, inscriptions can solve some mysteries surrounding a painting. The only reason the artist behind Landscape (1845), which is currently on view in Gallery 336, was discovered was because of what was found on the verso. Helen Matilda Kingman signed her name, the date, and her age—15—on the painting, which is the only painting by Kingman known to survive. She was visited by a travelling portraitist, Susan Catherine Moore Waters, who most likely inspired her to paint the serene, tropical landscape.

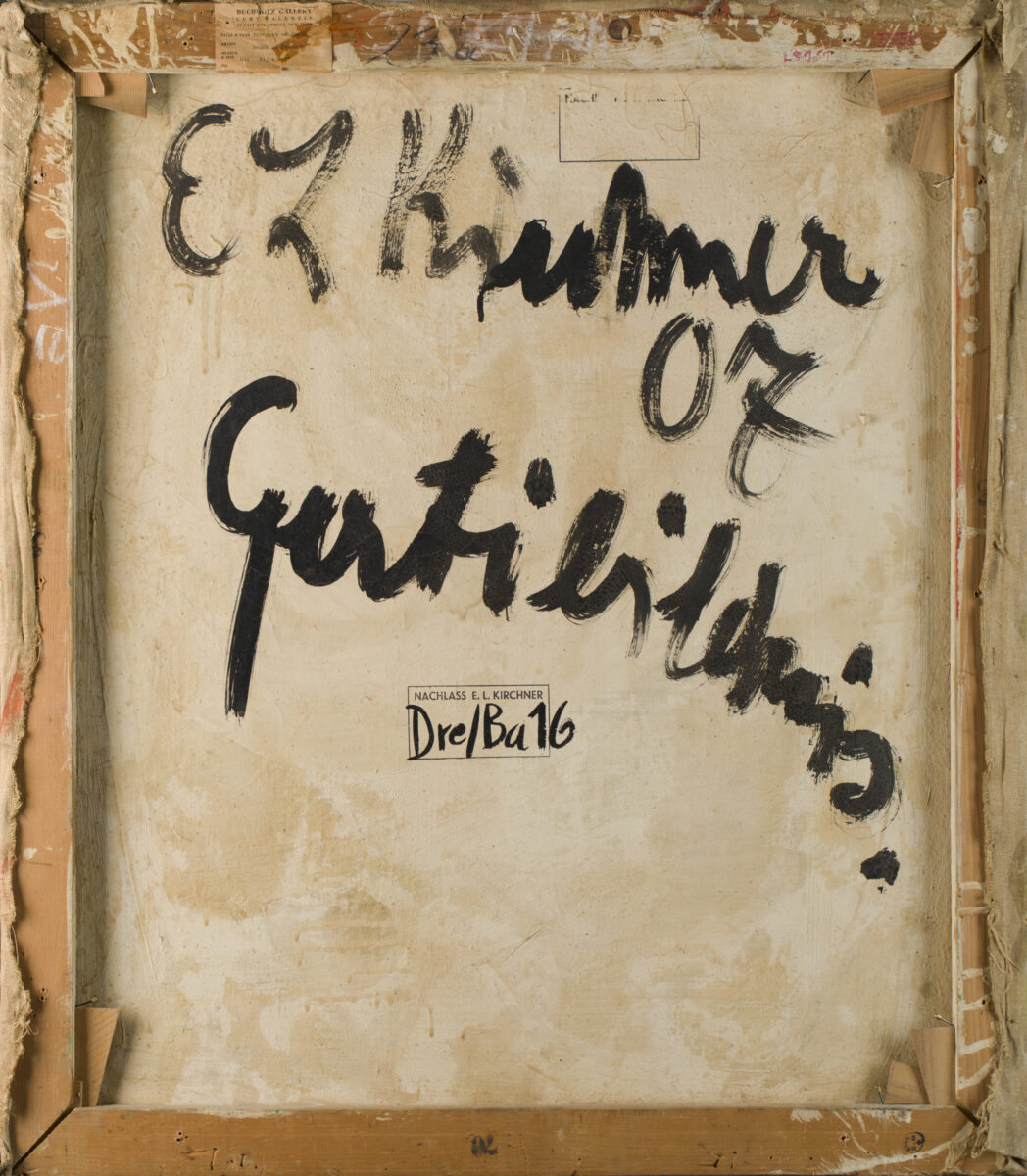

Conservation efforts that were part of research for a new catalogue on the Museum’s collection of German Expressionist paintings uncovered the once lost title on the back of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Portrait of Gerti. According to the catalogue, the sitter’s identity had eluded scholars, as the original title of the work had been unknown. The Museum historically exhibited it as Portrait of a Young Woman, referencing Donald Gordon’s catalogue raisonné from 1968.

-

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, German (active Switzerland), 1880–1938; Portrait of Gerti, dated 1907 [1910-11]; oil on canvas; 31 3/4 x 27 3/4 in. (80.6 x 70.5 cm); Saint Louis Art Museum, Given by Sam J. Levin and Audrey L. Levin 26:1992

-

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, German (active Switzerland), 1880–1938; "Portrait of Gerti" (verso), dated 1907 [1910-11]; oil on canvas; 31 3/4 x 27 3/4 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Given by Sam J. Levin and Audrey L. Levin 26:1992

Once the painting was removed from its frame, the artist’s fluid, expressive black script was revealed. Along with Kirchner’s signature and the year (1907), the back shows the title: “Gertibildnis,” or Portrait of Gerti. Because of this newfound information, the subject of the portrait is no longer shrouded in anonymity. Conservators and curators used clues from Kirchner’s whereabouts and personal relationships of the era to discover that “Gerti” likely is Armgart Grosse, the younger sister of the artist’s girlfriend at the time.

The painting, displayed in a case with its verso visible, is on view in Concealed Layers: Uncovering Expressionist Paintings, which highlights other conservation findings from the new catalogue.