Installation view of Modern and Contemporary Japanese Ceramics

Represented in the Museum’s global collection, Japanese potter Hamada Shōji had a significant impact on studio pottery. The artist was born in 1894 in Kawasaki, Japan. As a young adult, he attended Tokyo Institute of Technology, studying ceramics under Itaya Hazan, a Japanese artist widely considered a pioneer of modern Japanese ceramics. This elite education, alongside travel and collaboration with other potters like Bernard Leach, qualified Hamada to co-found the Leach Pottery, St Ives that became one of the most influential potteries in the world. Soon after, he opened his own pottery studio in Mashiko, Japan, a small community famously established as “pottery town” following his arrival in 1924. He cultivated his craft living in this small town while working as the head curator at the Japan Folk Art Museum in Tokyo. In 1974, Hamada founded the Mashiko Reference Collection Museum.

Shōji Hamada, 1971; Courtesy of Bonham’s

Hamada and Leach—who referred to his relationship with Hamada as that of soulmates—ushered in a new movement in contemporary ceramics known as mingei. The term translates to “art of the people” and is characterized by natural materials, daily use, and, often, anonymity of the artisan. It was coined by revered potter and philosopher Yanagi Sōetsu, who believed in the importance of appreciating the beauty and craftmanship of everyday ceramics made by the citizens of Japan who sculpted “free of ego and the desire to be famous or rich, merely working to earn their daily bread,” according to an essay by Yūko Kikuchi, author, curator, and professor at the Royal College of Art in London.

However, mingei does not include cheaply made, mass-produced daily objects. “In order to be called mingei an object must be wholesomely and honestly made for practical use,” made with thoughtful materials and close attention to detail, according to Yanagi in his book Sōetsu Yanagi: Selected Essays on Japanese Folk Crafts.

Initiated in 1926, the mingei movement gained popularity in the 1930s following the creation of the Mingei Association of Japan by Yanagi, Hamada, and renowned potter Kawai Kanjirō. In 1936, the trio founded the Japan Folk Crafts Museum in Tokyo, where Hamada would go on to work. Throughout the next four decades, Hamada continued his work, solidifying his legacy as a master of pottery. He mentored and lectured across the globe and was designated a Living National Treasure by the Japanese government in 1955, the first of many such designations for the best artists and craftsmen in the country. Hamada passed away in 1978.

A new installation in the Oliver and Mary Langenberg Gallery 225 and part of Mr. and Mrs. John Peters MacCarthy Gallery 226, Modern and Contemporary Japanese Ceramics highlights works by Hamada and his contemporaries—some now deceased and many others still living. Ranging from earthenware to stoneware, porcelain to Chinese-inspired glazes, this long-term installation presents the vibrancy of Japanese ceramics in the SLAM collection. The various works showcase an extraordinary range of firing techniques, sculptural forms, and impeccable glazes.

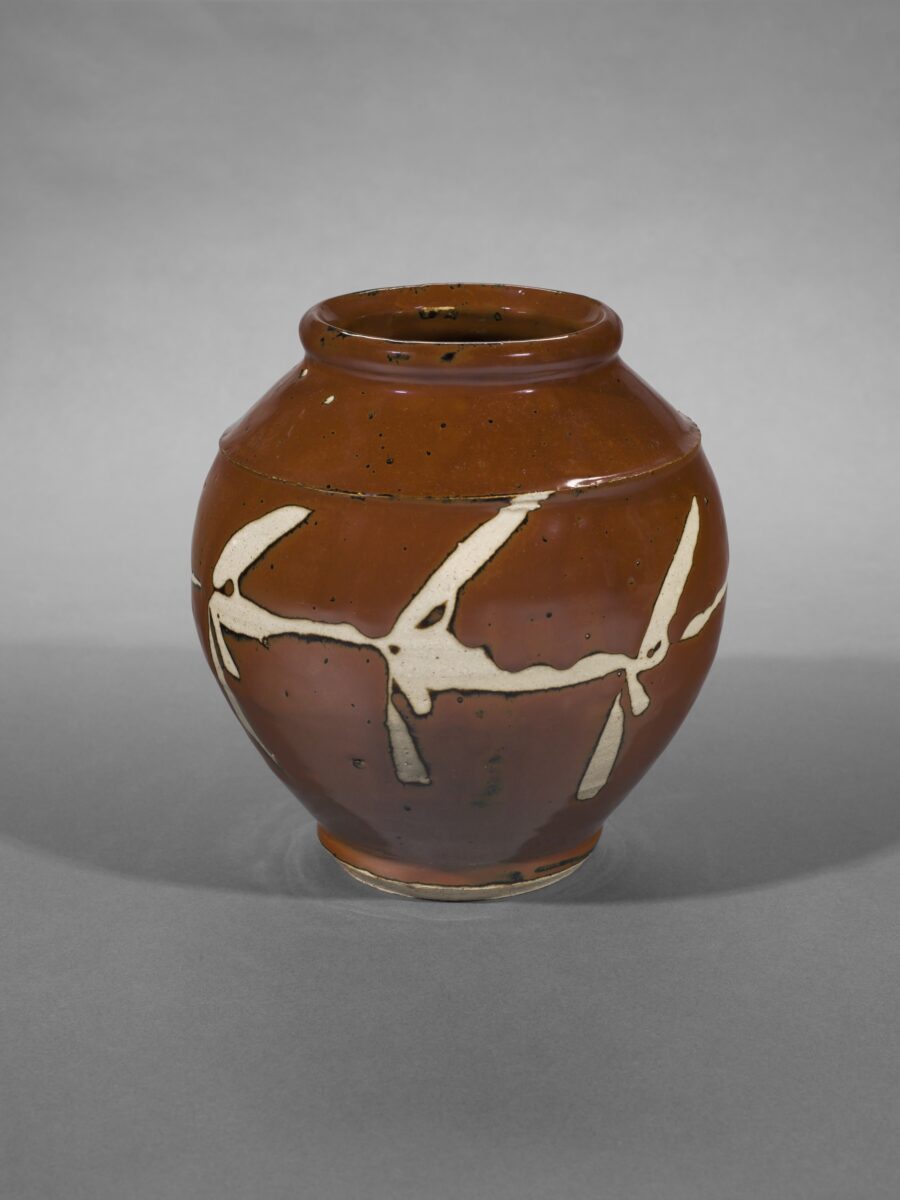

Three of Hamada’s works are featured prominently in the presentation. On view near the entrance of Modern and Contemporary Japanese Ceramics, the exceptional stonewares showcase the artist’s lifelong commitment to mingei pottery. Hamada’s Rectangular Footed Dish (tetsu-e kaku moribachi), shown above, was hand-decorated in the early 1960s in his famous Mashiko studio. Square Bottle (tetsu-e kakubin) and Flower Vase with Wax-Resist Design (kakiyū nuki-e kabin), made in the early and mid-1950s, use similar techniques as well as materials sourced from Mashiko. Each work highlights Hamada’s appreciation of functional wares made using traditional methods, such as celadon glaze and underglaze iron decoration.

To view these works as well as pieces from other Japanese ceramicists, including Matsui Kōsei, Ide Teruko, and Ogino Masuko, visit Modern and Contemporary Japanese Ceramics on Level Two of the Museum.

-

Hamada Shōji, Japanese, 1894–1978; Rectangular Footed Dish (tetsu-e kaku moribachi), c.1963; Mashiko ware; stoneware with celadon glaze and underglaze iron decoration; 3 3/16 x 8 3/4 x 12 3/4 in.; Saint Louis Art Museum, Funds given by Patricia H. Clark, Mary P. Oenslager Foundation Fund, Mrs. Perry T. Rathbone and family, and others in memory of Perry T. Rathbone, and General Acquisition Funds 104:2002; © Estate of Hamada Shoji

-

Hamada Shōji, Japanese, 1894–1978; Flower Vase with Wax-Resist Design (kakiyū nuki-e kabin), c.1950; Mashiko ware; stoneware with persimmon (kaki) glaze and wax-resist brushwork; 8 3/4 in. × 8 1/4 in.; Saint Louis Art Museum, Funds given by Bernard and Sally Lorber Stein and Museum Purchase 4:2000; © Estate of Hamada Shoji

-

Hamada Shōji, Japanese, 1894–1978; Square Bottle (tetsu-e kakubin), 1955; Mashiko ware; stoneware with colored glazes and iron decoration; 9 1/4 × 3 7/8 × 3 7/8 in.; Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of Bernard and Sally Lorber Stein 20:1999; © Estate of Hamada Shoji