Courtney Books examines Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's Portrait of Gerti under a stereo microscope to see the underlying layers of paint.

Concealed Layers: Uncovering Expressionist Paintings presents new discoveries made during an ambitious three-year study of the Museum’s world-class collection of German Expressionist paintings. Complete underpaintings, a lost title, and studio graffiti are just some of the exciting findings that will receive their public debut.

Exhibition curators Courtney Books, associate paintings conservator, and Melissa Venator, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Assistant Curator of Modern Art, have answered a few questions about the free exhibition, which is on view through October 27.

Courtney Books, associate paintings conservator, and Melissa Venator, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Assistant Curator of Modern Art

What are some characteristics of German Expressionism?

Venator: There’s a common misconception about Expressionist art that it’s all harsh, jagged angles and clashing colors. In fact, figurative styles were the rule, and colors really varied by artist. This diversity makes sense, considering that the movement was active for three decades and encompassed hundreds of artists. Whatever your taste in art, there’s probably an Expressionist whose work you’ll enjoy.

I love total abstraction, so my favorite in the exhibition is Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s Rising Moon. He made it during a brief period from 1910-1912 when he was painting with a really limited palette of fantastically bold colors. The scene is a farmyard at night with a barn and two haycarts, but he’s simplified it so much that it’s hard to make out the subject. He balances perfectly between figuration and abstraction. I like to stand in front of it and imagine him at work in his studio.

-

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, German, 1884–1976; Rising Moon, 1911–12; oil on canvas; 34 7/8 x 37 7/8 in. (88.6 x 96.2 cm); Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May 938:1983

-

Vassily Kandinsky, Russian (active Germany), 1866–1944; Murnau with Locomotive, 1911; oil on canvas; 37 3/4 x 41 1/8 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May by exchange 142:1986

-

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, German (active Switzerland), 1880–1938; Portrait of Gerti, dated 1907 [1910-11]; oil on canvas; 31 3/4 x 27 3/4 in. (80.6 x 70.5 cm); Saint Louis Art Museum, Given by Sam J. Levin and Audrey L. Levin 26:1992

Can you explain a few of the key conservation techniques applied to these works?

Books: Some of the most useful analytic techniques start at the surface. A powerful tool is ultraviolet (UV) light, known as black light. Under UV, materials emit colorful bursts of energy, called fluorescence, transforming paint into psychedelic palettes. This technique helps to identify specific pigments, oils, and resins by characteristic glow. Vasily Kandinsky’s use of white paint in Murnau with Locomotive appears deceptively simple, but UV highlights transform the white into interweaving yellows and pinks.

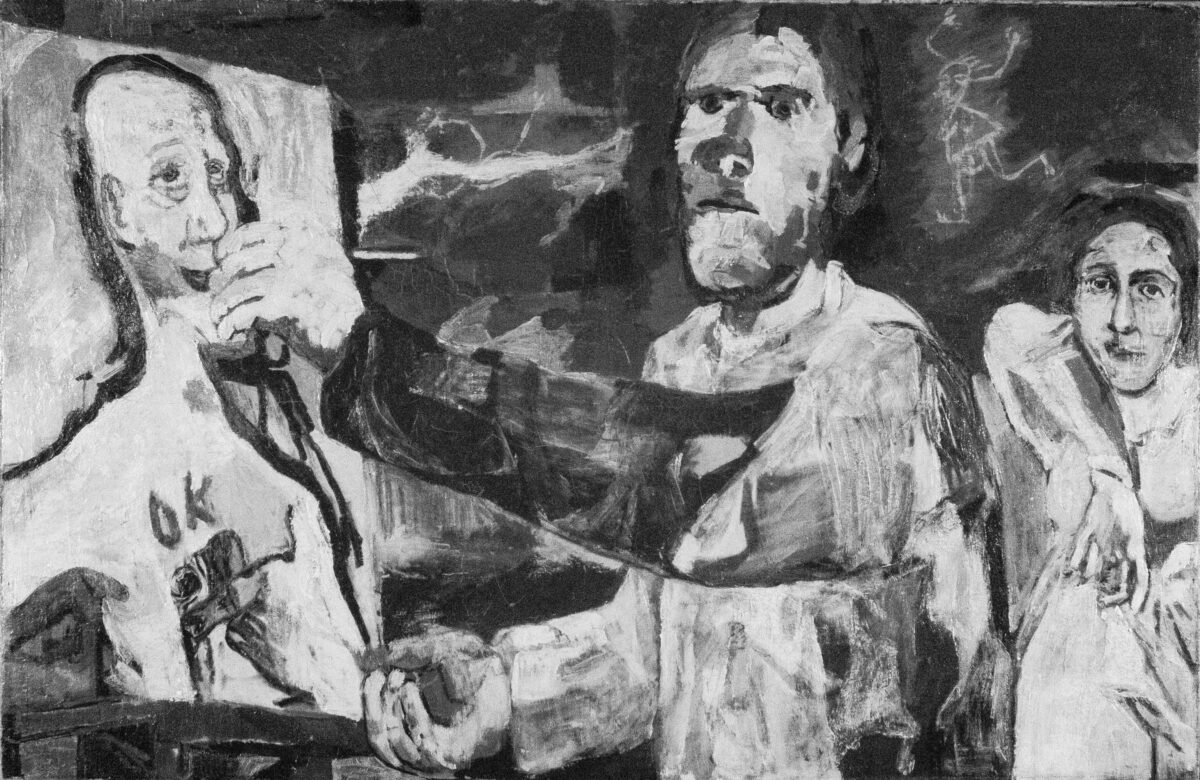

Complex techniques like infrared reflectography (IRR) and X-radiography allow for a deeper dive into a painting’s layers. With IRR, some paints become transparent while other materials, such as graphite, are detected. Specially adapted cameras can capture an underdrawing or underlying paint layers. Using IRR, the green paint in Oskar Kokoschka’s The Painter II (The Painter and Model II), goes transparent to reveal hidden stick figures covered by the artist.

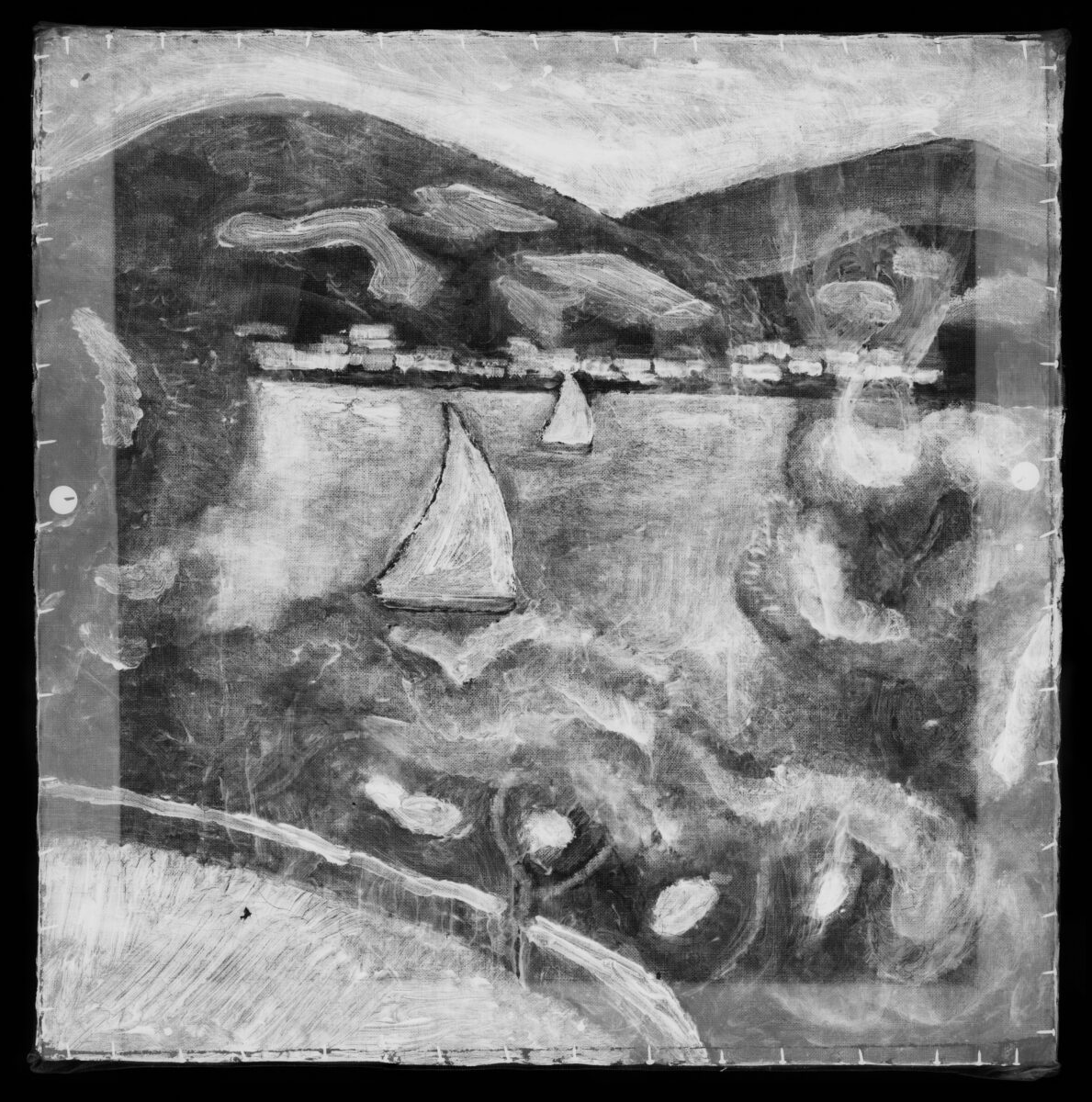

Where medical X-radiography reveals the bones and tissue of a person’s arm, an X-radiograph can expose a painting’s wooden support and metal hardware. If you’re lucky, an unexpected composition is revealed for the very first time, such as the landscape and figure lying within The Painter II.

-

Courtney Books examines Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's Portrait of Gerti under a stereo microscope to see the underlying layers of paint.

-

Melissa Venator examines Alexei Jawlensky's Prophet (Sibyl) under an ultraviolet light.

-

Melissa Venator studies an X-radiograph for George Grosz's Café on a lightbox.

-

Courtney Books examines Vasily Kandinsky's Murnau with Locomotive under a stereo microscope to see the underlying layers of paint.

Can you detail one of the more surprising findings from the conservation efforts?

Books: Rediscovering details lost over time is always rewarding. Each painting received an in-depth study in the lab. As I described the materials or condition revealed by each technique, Melissa related archival details and the artist’s known working methods. Emile Nolde’s Woman (in Strong Light) was documented as signed, but over time the script, painted an alizarin purple, grew closer in appearance to the background purples. When lit up boldly under UV, a cursive “Nolde.” suddenly appeared—a satisfying moment of “there it is!”

I was also simply delighted by the dynamic “studio graffiti” stick figures captured with IRR just below the surface of Kokoschka’s The Painter II—they’re so very expressive.

Venator: This is less of a specific finding and more of a general takeaway. What surprised me most was how much conservation has to teach us about these paintings. They’ve been at the Museum for decades now, and many are icons that have been the subject of major studies. But when I saw the underpainting of George Grosz’s Café in an X-ray or the photograph of the painting on the back of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Circus Rider, I learned that we can study a painting for years without really knowing it. Conservation gives us that insight.

-

Oskar Kokoschka, Austrian (active Germany and Switzerland), 1886–1980; The Painter II (Painter and Model II), 1923; oil on canvas; 33 1/2 x 51 1/4 in. (85.1 x 130.2 cm) framed: 42 3/4 x 60 1/2 x 2 3/4 in. (108.6 x 153.7 x 7 cm); Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May 910:1983

-

Oskar Kokoschka's The Painter II (Painter and Model II) seen using infrared reflectography, which revealed hidden stick figures.

-

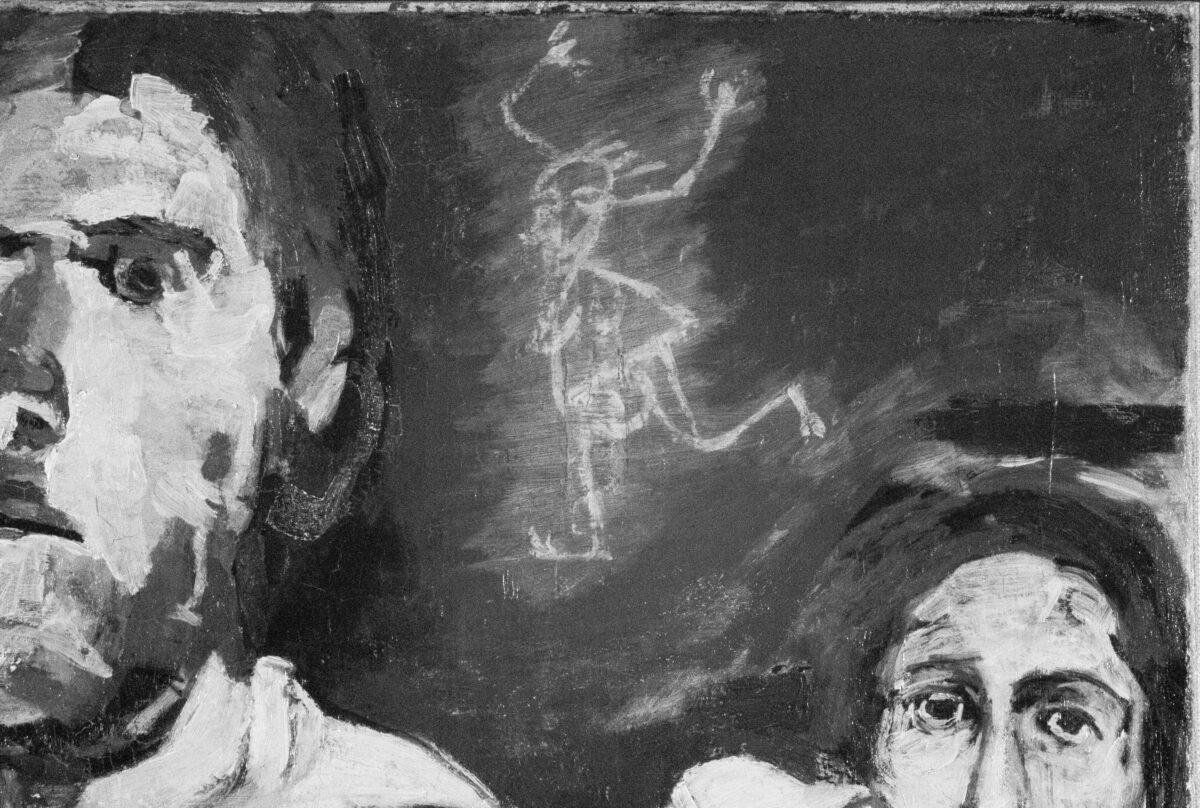

A detailed shot of the stick figure exposed using infrared reflectography on Oskar Kokoschka's The Painter II (Painter and Model II).

Did the conservation and curating process change your understanding of these works and/or artists? How?

Venator: Certainly some jaw-dropping infrared images and X-rays came out of the study, and we’ve shared those in the exhibition. But the most exciting part of this process for me was the challenge of translating the behind-the-scenes work into an engaging and informative exhibition for visitors. Courtney and I wanted to foreground the conservation images, rather than treat them as secondary illustrations. And we tried to bring the process into the galleries as much as possible with materials and equipment.

To answer your question more directly, the process gave me invaluable insight into practical decisions that the artist made in their studio a century ago. Most visitors ask two questions about an artwork: “What does it mean?” and “How was it made?” The first question is almost impossible to answer, because we’ll never know the artist’s intent. As an art historian, I can make some educated guesses and give useful historical context. Conservation, at least, gives us some objective data about how an artwork was made. And sometimes, like with the paintings in this exhibition, those discoveries form the basis of entirely new interpretations.

What do you hope exhibition attendees will learn through seeing these works and conservation images?

Books: Art projected through the lens of science creates some fun intersections. When technical analysis is an available resource and promoted, there is always more to learn about these paintings and how they were made. Artists such as Kandinsky, Schmidt-Rottluff, or Kirchner clearly labored over their calculated compositions, paint textures, and vibrant color choices. Expressionism may appear deceptively straightforward at a quick glance. This exhibition and research hopefully dismantle any such impression.