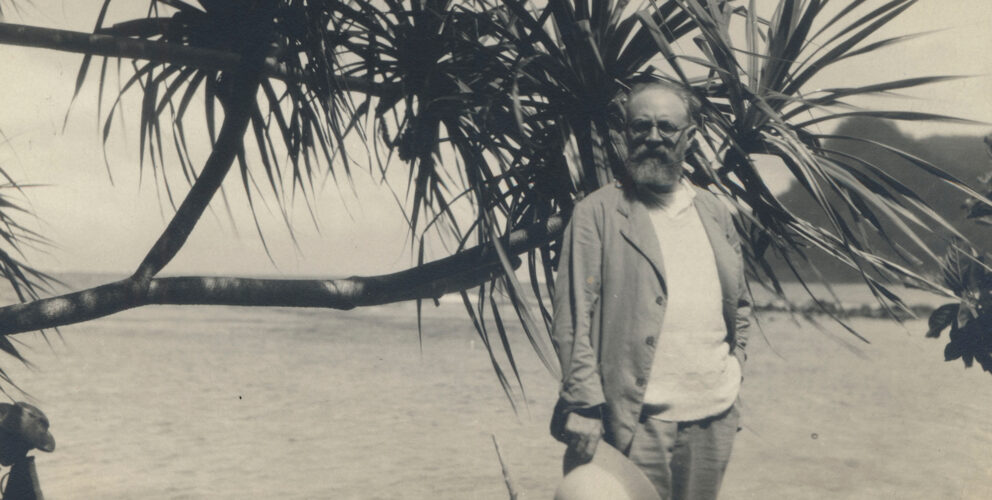

Matisse in Tahiti (detail), 1930; Archives Henri Matisse, all rights reserved; Photo: F. W. Murnau

The Saint Louis Art Museum’s first ticketed presentation of 2024 is Matisse and the Sea. The multimedia exhibition is the first to examine the significance of the sea across modernist artist Henri Matisse’s career, which included artwork in coastal locations on the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, and the Pacific.

Simon Kelly, SLAM’s curator of modern and contemporary art, has answered a few questions about the exhibition in advance of its February 17 opening.

Matisse and the Sea is on view through May 12.

Simon Kelly, curator of modern and contemporary art

What was Matisse’s relationship with the sea, and how did it impact his work?

Kelly: Matisse loved the sea—its color, its light, its movement—and it was the catalyst for some of the most important work in his career. He mainly painted the Mediterranean Sea, but as this exhibition demonstrates, he also depicted the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. One of the interesting things about Matisse’s relationship with the sea was that it was very physical and visceral. He was a great swimmer and an accomplished rower, and for me, that really complicated the conventional idea of Matisse as being very cerebral and almost professorial. The exhibition features a wide range of his images of the sea, from early views of the Mediterranean coast to late cut-outs inspired by French Polynesia. Matisse traveled very extensively and often to islands and seaside resorts in search of new inspiration. Early on, you mainly see panoramic views of the sea, but later, you see his growing interest in recreating life beneath the waves, a kind of oceanic paradise teeming with fish life, coral, and algae.

Henri Matisse, French, 1869–1954; Bathers with a Turtle, 1907–1908; oil on canvas; 71 1/2 x 87 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Pulitzer Jr. 24:1964; © 2013 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

SLAM’s iconic Bathers with a Turtle is showcased in this exhibition. What makes this work so important in terms of Matisse’s oeuvre and the museum’s collection?

Kelly: I think Bathers with a Turtle is so important because it’s made at a really pivotal moment in Matisse’s artistic career. You can see him literally shifting from naturalism to abstraction in his work on the canvas, as he removes the fishing boats and hills and clouds in the background to create three flat abstract bands of color. At the same time, his work on the bathers themselves shows his radical engagement with a range of new avant-garde influences from sub-Saharan African sculpture to the paintings of Paul Cezanne. These fused elements come together in SLAM’s work in a way that was profoundly important for Matisse’s later practice and more generally for the history of 20th-century art. The painting had an impact not only on French Fauve painters but also the German Expressionists and American Abstract Expressionists. Bathers with a Turtle is really the Mona Lisa of the modern collection.

Henri Matisse, French, 1869–1954; Blue Nude I, 1947; gouache, painted paper cut-outs on canvas; 41 7/8 x 30 11/16 inches; Foundation Beyeler Collection, Inv.60.1; © 2024 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The exhibition includes a wide range of media; how did Matisse’s work evolve over the course of his career?

Kelly: Matisse loved to experiment with different media. In his early years, he focused on his painting, creating works of pure color that are generally known as Fauve, a word which literally translates as “wild” and which speaks to the way that his brightly colored, profoundly non-naturalistic paintings originally shocked the public. Sculpture was also a key part of his early practice, and it’s great that we have major examples of his early sculpture in the show. The most significant new medium that he began to use later in his career was the paper cut-out. These might be among Matisse’s best-known works today. Initially Matisse intended them as studies, but as his health failed and he could no longer paint and sculpt, they became the focus of his practice. In this exhibition, we have some wonderful examples of Matisse’s late cut-outs including the iconic and rarely lent Blue Nude I.

Pende artist, Democratic Republic of the Congo; Giwoyo Mask, 19th-early 20th century; wood, pigment and organic materials; 25 9/16 x 9 13/16 x 8 11/16 inches; Administration Jean Matisse, Paris

African sculptures and masks are included in the exhibition; what role did these types of works have on Matisse’s practice?

Kelly: I think that African sculptures and masks have an absolutely central role in Matisse’s practice. He first began to collect them in 1906, and over time, he built up a significant—if relatively small—collection, a number of examples of which we have in the exhibition. They provided a completely different way of representing the human form to the European naturalistic tradition in which he’d been trained. African sculptures and masks abstract from the human body and have a very stylized sense of geometry. For Matisse, I think they opened his eyes to a new approach to modeling the human form. It’s important to realize that I don’t think he really ever understood the original function of these objects, and we try to explain that function in the exhibition. Rather, he was inspired by their radical formal qualities. Take the example of our painting, Bathers with a Turtle: Look at the angularity of line, the elongation and extension of limbs, particularly the feet, and the central figure’s pose with hands pulled up to chin. All of those are elements I think Matisse took from sub-Saharan African sculpture.

Henri Matisse, French, 1869–1954; Collioure (La Moulade), 1906; oil on canvas; 11 1/8 x 14 inches; Private Collection; © 2024 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

How has curating this exhibition changed your understanding of Matisse and his works?

Kelly: Curating this exhibition has really made me realize the globalism of Matisse’s work and outlook. Throughout his career, he was open-minded to different, often non-Western, artistic traditions, from African sculpture and textiles to Oceanic tapa cloth and war shields. It should be said, however, that this was often within a French colonial framework, and the accompanying power dynamic between colonizer and colonized. Matisse used, or you could say appropriated, aspects of these traditions in his own work. In this show, we’ve brought together Matisse’s works with different aspects of African and Oceanic artistic traditions, whether Kuba artist prestige cloth from Congo or a shield made by an Abau artist in Papua New Guinea. The sea functions as a kind of metaphor for the importance of travel around the world for Matisse and his experience of diverse cultures.