August Macke, German, 1887–1914; Landscape with Cows, Sailboat, and Painted-in Figures(detail), 1914; oil on canvas; 20 1/4 × 20 1/4 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May 911:1983

The Saint Louis Art Museum’s global collection contains more than 700 artworks by the German Expressionists—one of the strongest holdings in the country—and the world’s largest grouping of paintings and prints by Max Beckmann.

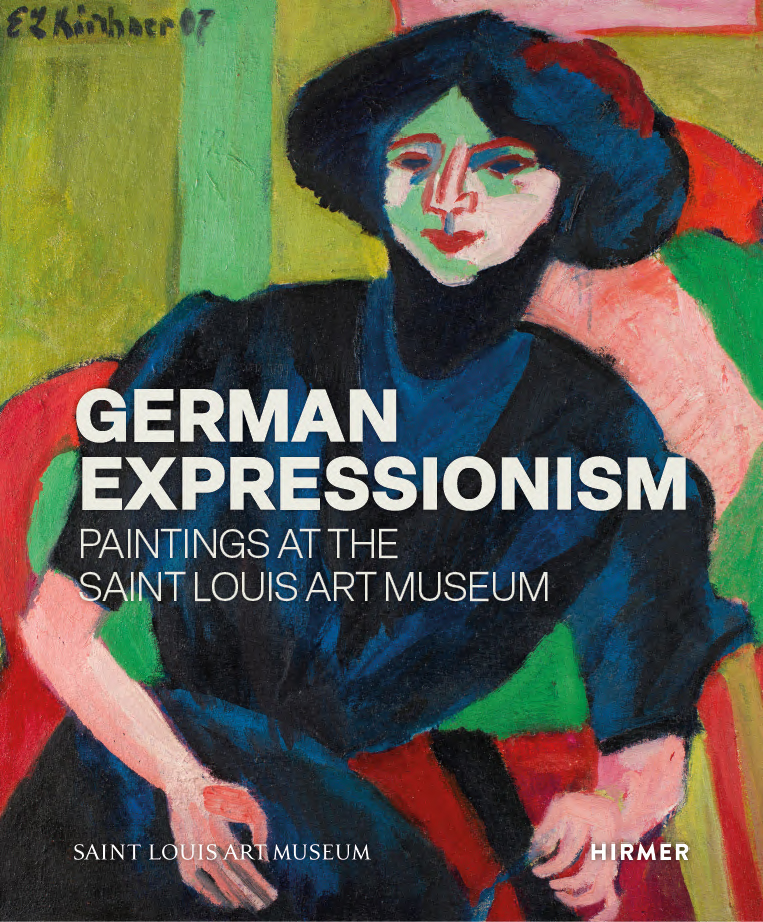

SLAM’s new publication German Expressionism: Paintings at the Saint Louis Art Museum gives an overview of the movement and closely examines 48 works that were made from 1905 to 1939 by more than two dozen artists. Their styles and subjects span the arc of the well-known movement. The book is a companion to Max Beckmann at the Saint Louis Art Museum: The Paintings, which was published in 2015.

But what is Expressionism?

From the start, there’s been little consensus on the movement’s origins or aims, and many of the artists labeled as Expressionist in the press rejected the designation. The word was first used by art critics in 1911, and the art-viewing public understood “Expressionism” as a repudiation of Impressionism. Expressionism’s mass appeal changed the course of German art in the second decade of the 20th century.

“Subjects became more abstracted from nature; colors, more intense and unnatural; and forms, flatter with heavy outlines,” catalogue author Melissa Venator, SLAM’s Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Assistant Curator of Modern Art, wrote in the book’s introduction. “But what caused critics in Germany to really take notice was how quickly this new art appeared. Almost overnight, it seemed that every artist under 30 had abandoned Impressionism, Naturalism, and Symbolism, and in their place was art that shocked and outraged.”

Alexei Jawlensky, Russian (active Germany), 1864–1941; Spring, 1912; oil on cardboard; 26 x 19 3/4 in. (66 x 50.2 cm); Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May 896:1983

Expressionism began in the years after 1900 with a generation of artists born between 1870 and 1890 who worked in almost total anonymity, alone and in small groups, to develop a new type of art. A proliferation of official and unofficial collectives acting as incubators for the new art marked Expressionism before World War I. The most prominent were Brücke—that included well-known names like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Max Pechstein—and Blue Rider, which featured artists such as Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Auguste Macke.

Just as the movement achieved a degree of acceptance, World War I began, marking a turning point for the Expressionists. The German Empire’s loss brought political revolution and the installment of a constitutional republic, along with prolonged street violence and economic collapse. At the same time, the Expressionists became more well-known and began teaching at the same academies that once rejected them, marking the beginning of the end of Expressionism as the avant-garde of modern art in Germany.

Under the Nazi regime (1933-1945) though, Expressionism and its artists became targets of a crusade against modernism. German museums removed thousands of Expressionist artworks from their collections and displayed a selection in the 1937 propaganda exhibition Degenerate Art.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, German, 1876–1907; Two Girls in Front of Birch Trees, c.1905; oil on artist board; 21 3/4 x 13 7/8 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May 914:1983

“After the exhibition closed, the art removed from the museums was sold on the international market or lost, presumed destroyed in the bombings of German cities at the end of the war,” Venator wrote. “Many artists who stayed in Germany lost their early works when bombs hit their homes and studios. The Expressionist paintings in collections today are the rare survivors of a 13-year campaign to erase all traces of the movement.”

Why St. Louis?

Naval officer Morton D. May returned home to St. Louis after World War II and became an executive in his family’s department store empire. He also developed a deep passion for art. In a trip to New York in 1951, May noticed a collection of Expressionist paintings and watercolors in a gallery that he’d seen there years before. He wondered why they’d gone unsold and purchased the works, thus beginning his “one-man crusade to see that German expressionism was given its rightful position in modern art.”

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, German, 1884–1976; Rising Moon, 1911–12; oil on canvas; 34 7/8 x 37 7/8 in. (88.6 x 96.2 cm); Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May 938:1983

By the time of this purchase, May had already begun to collect the works of Max Beckmann, who he called one of the best painters of the 20th century. In the early years of his collecting, May purchased so much art so quickly that he was able to open an exhibition of 35 paintings by Beckmann and the Expressionists at the Arts Club of Chicago in November 1951. Low prices led to his rapid purchasing, which he attributed to the movement’s unpopularity in the United States—whether from conservatism, unfamiliarity, or anti-German sentiment at World War II’s end.

May died in 1983 and left much of his collection to the Saint Louis Art Museum. In addition to all but 10 of the German Expressionist paintings featured in the German Expressionism book, May also collected and gifted thousands of works of African, Oceanic, and ancient American art, and American and European modern and postwar paintings, sculpture, and works on paper to the Museum. He remains the single largest donor of art in SLAM’s history.

James D. Burke, who was the director at the time of May’s death, described his bequest as “one of the most important gifts of art ever made to an American art museum,” and works he gave still have pride of place in the galleries today. Some Museum fixtures that passed through May’s hands include Otto Mueller’s Three Women in a Wood, Franz Marc’s The Little Mountain Goats, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Circus Rider, and Vasily Kandinsky’s Murnau with Locomotive (read more about recent conservation treatment on the Kandinsky painting in an earlier blog post) among many, many others.

"Man of the Year: Morton D. May," [St. Louis] Globe-Democrat Sunday Magazine, December 27, 1959; St. Louis Mercantile Library, University of Missouri-St. Louis

Other St. Louis collectors—like Joseph Pulitzer Jr. and Audrey and Sam Levin who would eventually gift works to the Museum—also took advantage of the low price tags on German Expressionist paintings in the early 1950s. This collecting inspired future Museum directors to continue May’s legacy by acquiring German art, including contemporary works by artists who were inspired by the Expressionists.

“Thanks to those efforts, the Museum has fulfilled May’s original vision to create the nation’s most complete collection of German art of the 20th century for St. Louis,” Venator wrote.

More information on SLAM’s collection of German Expressionist art, including essays featuring discoveries made during technical analysis of the works, can be found in the 300-page, beautifully illustrated catalogue German Expressionism: Paintings at the Saint Louis Art Museum. The book is available for purchase online and in Museum shops, and it spurred an exhibition opening in March 2024, Concealed Layers: Uncovering Expressionist Paintings, which examines this important collection area from an arts-conservation angle.