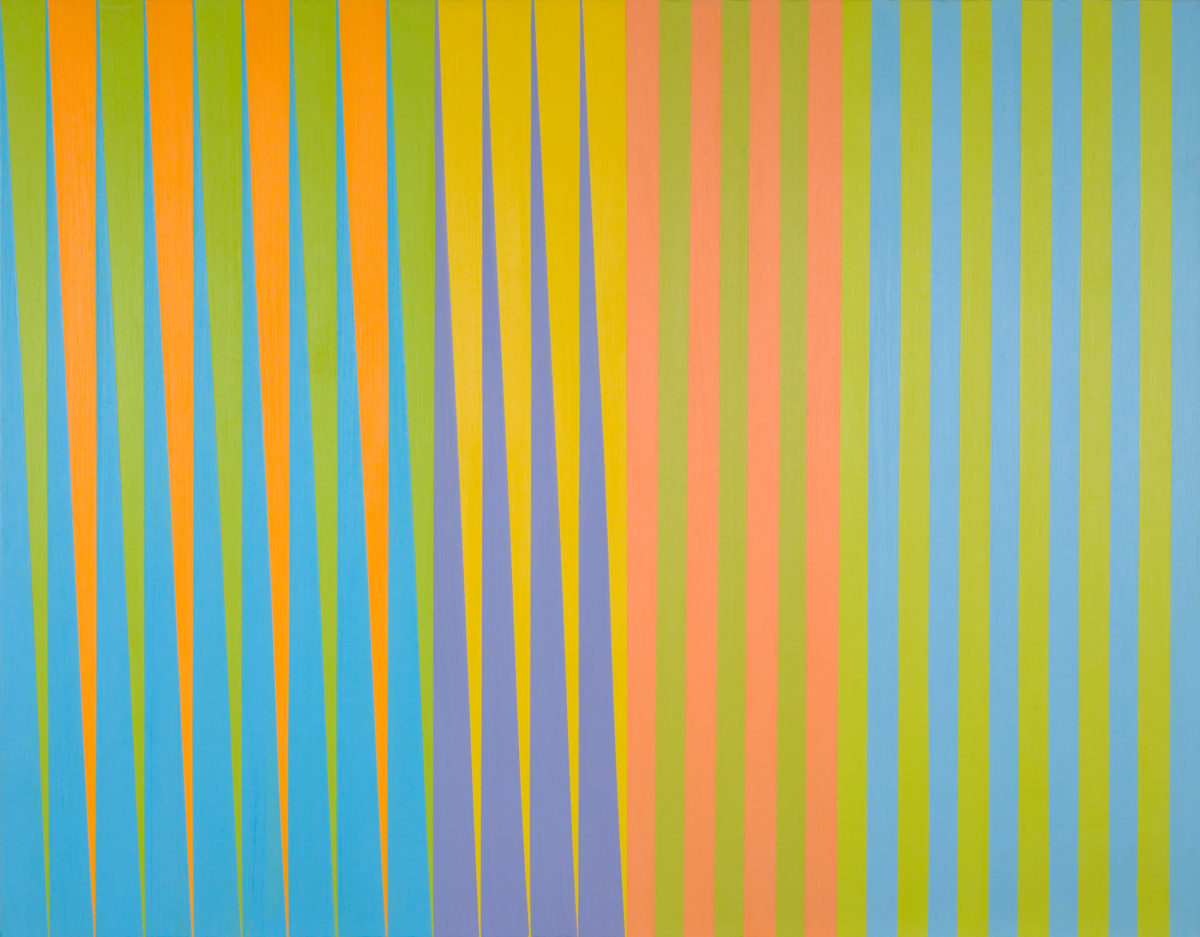

Double Exposure

- Material

- Oil and wax on canvas

James Little, American, born 1952; Double Exposure, 2008 (detail); oil and wax on canvas; 39 x 50 inches; The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 190:2017; © June Kelly Gallery / James Little

The Shape of Abstraction: Selections from the Ollie Collection presents paintings, drawings, and prints by five generations of black artists who have revolutionized abstract art since the 1940s. The exhibition includes Norman Lewis’s gestural drawings, Sam Gilliam’s radically shaped paintings, James Little’s experiments with color, and Chakaia Booker’s explorations in printmaking, among many others. Despite their significant contributions, many of these accomplished artists have remained largely under recognized and omitted from the existing narrative of art history. However, the reexamination and celebration of this history is underway.

In 2017, St. Louis native Ronald Ollie and his wife, Monique, gave the Saint Louis Art Museum a transformative collection of 81 works by black abstractionists. Ollie, who passed away in June 2020, spent decades collecting, often befriending the artists and forming long, collaborative relationships. He grew up visiting the Museum with his parents, who nurtured his deep appreciation for art. This exhibition draws from and celebrates the Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, which was named in honor of his parents.

The Shape of Abstraction: Selections from the Ollie Collection was curated by Gretchen L. Wagner, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs; and Alexis Assam, 2018–2019 Romare Bearden Graduate Museum Fellow.

The five generations of artists represented in this exhibition revolutionized abstract art from the 1940s to the present. Their innovations with form, color, process, and materials are paramount to the development of Abstract Expressionism and art movements that followed. Despite their significant contributions, many of these accomplished figures, all of whom are black artists working in the United States and abroad, have remained largely under recognized and omitted from the existing narrative of art history.

As artists of African descent negotiating racial inequality, they were often denied entry to the exhibition opportunities and professional circles enjoyed by their famed American and European peers. Moreover, dedicated to abstraction, they encountered additional divisions with other black artists who insisted on addressing issues of identity and struggle through representational art. Facing such headwinds, these abstractionists forged their own networks, fostering connections with each other, as well as curators, scholars, dealers, and collectors, to support creative production and critical discourse. The exhibition—its title based on the Quincy Troupe poem—features a selection of works from the Ollie gift.

Many artists included in this exhibition sought exposure to foreign cultures and landscapes. At various points in their careers, they actively pursued opportunities to travel or even permanently relocate abroad. For 20th-century black American artists, life outside the United States could offer freedom from the debilitating limitations imposed by the discrimination they encountered at home.

Considered a leading venue of modern art, Paris remained a destination of choice for many artists even after World War II (1939–1945). The artists Herbert Gentry, Ed Clark, Robert Blackburn, Larry Potter, and Sam Middleton each resided there during the 1940s and 1950s. As US military veterans, several utilized G.I. Bill subsidies to attend the city’s prestigious art schools and establish their own studios in this art capital.

Daily life in the battered city of Paris, plagued by food rations and intermittent heat and electricity, proved challenging. However, access to many founders of abstraction, including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Constantin Brancusi, and the intellectual exchange fostered in the vibrant café culture were exceptionally formative. Gentry, Clark, and Middleton lived and worked abroad for decades, seeking inspiration for their art from their newfound environments.

Robert Blackburn, American, 1920–2003; Faux Pas, 1960; lithograph; sheet: 30 × 22 1/8 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 121:2017; © The Estate of Robert Blackburn

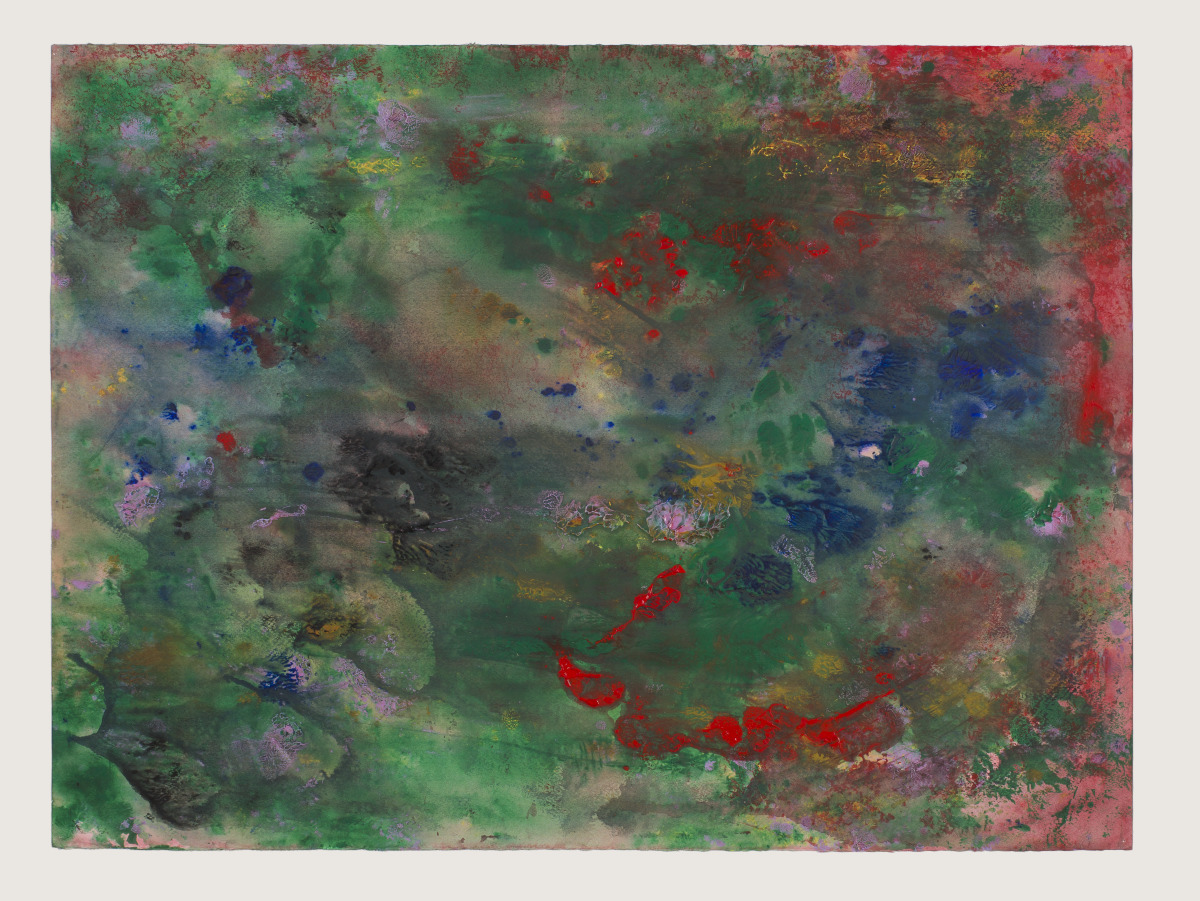

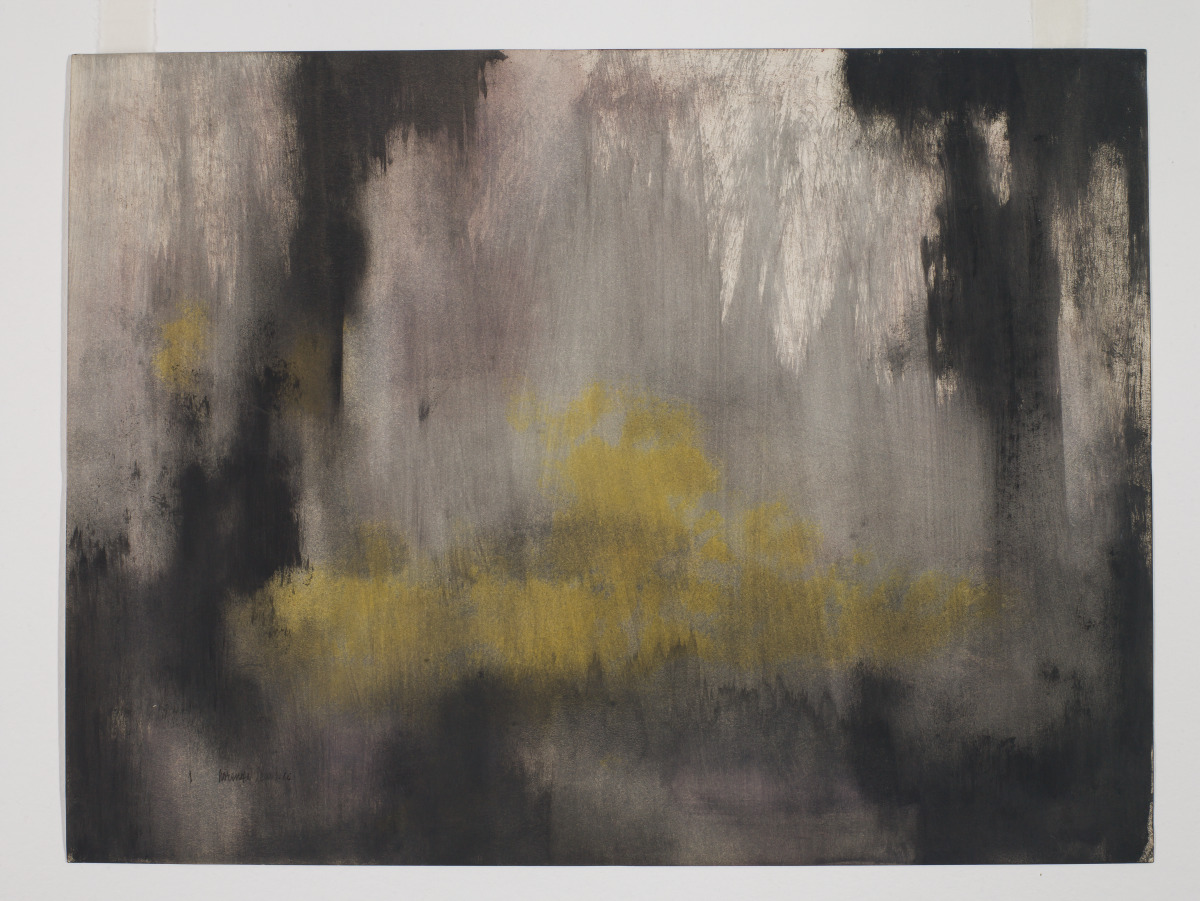

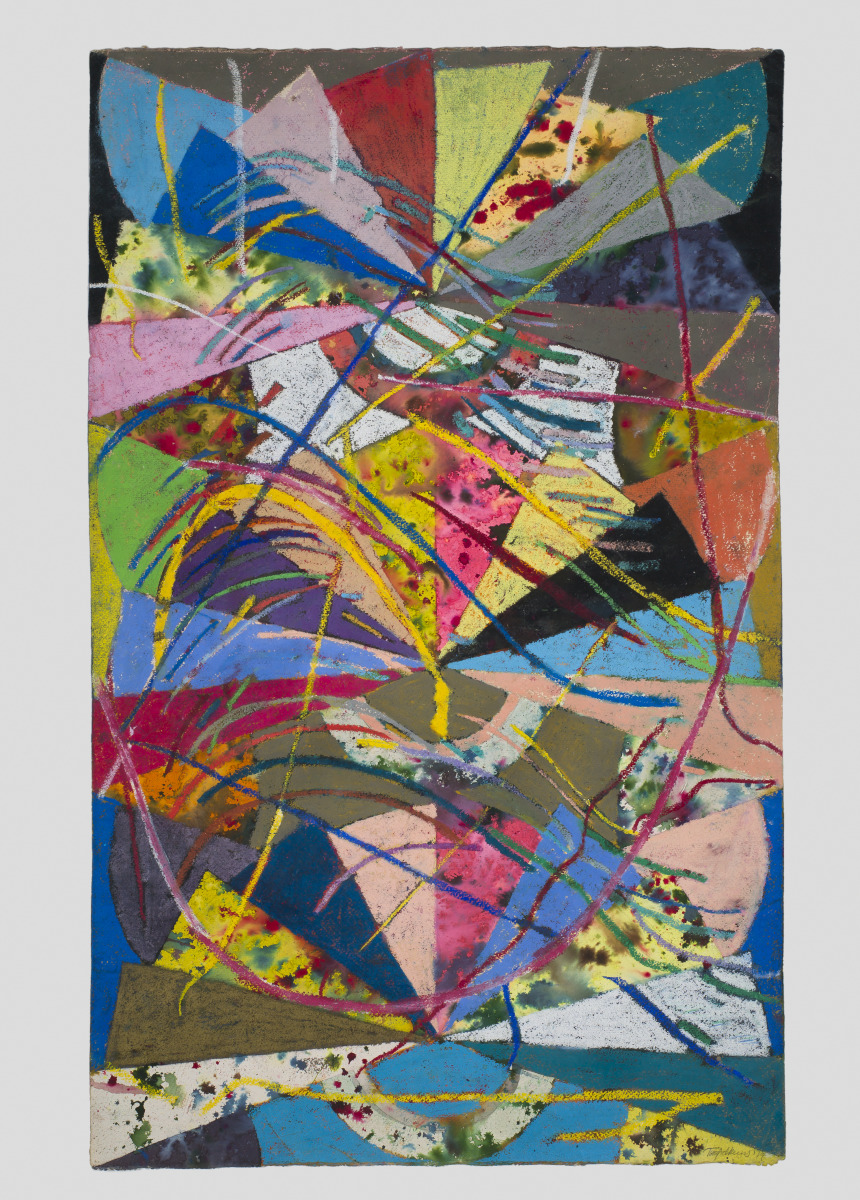

Untitled (Bahia Series), 1988

Ed Clark, American, born 1926

dry pigment

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 130:2017

© Ed Clark / Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

Untitled, n.d.

Larry Potter, American, 1925–1966

gouache and acrylic

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 178:2017

© Larry Potter

Out into the Open, 2000

Stanley Whitney, American, born 1946

acrylic on canvas

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 193:2017

© Lisson Gallery / Stanley Whitney

III, 2001

Winston Branch, British (born St. Lucia), born 1947

gouache and oil

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 123:2017

© Winston Branch

Untitled, 1990

Sam Middleton, American, 1927–2015

collage of cut and torn printed and painted papers, with paint and graphite

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 174:2017

© Sam Middleton estate; Courtesy of Spanierman Modern

Sunset, 1997

Evangeline Montgomery, American, born 1933

offset lithograph

published and printed by Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 176:2017

Courtesy the artist Evangeline J. Montgomery and Galerie Myrtis; © Evangeline Montgomery

Untitled, 1971

Herbert Gentry, American, 1919–2003

ink

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 149:2017

© Mary Anne Rose and the Estate of Herbert Gentry

Untitled, 1974

Herbert Gentry, American, 1919–2003

graphite

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 147:2017

© Mary Anne Rose and the Estate of Herbert Gentry

Faux Pas, 1960

Robert Blackburn, American, 1920–2003

lithograph

published and printed by the artist

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 121:2017

© The Estate of Robert Blackburn

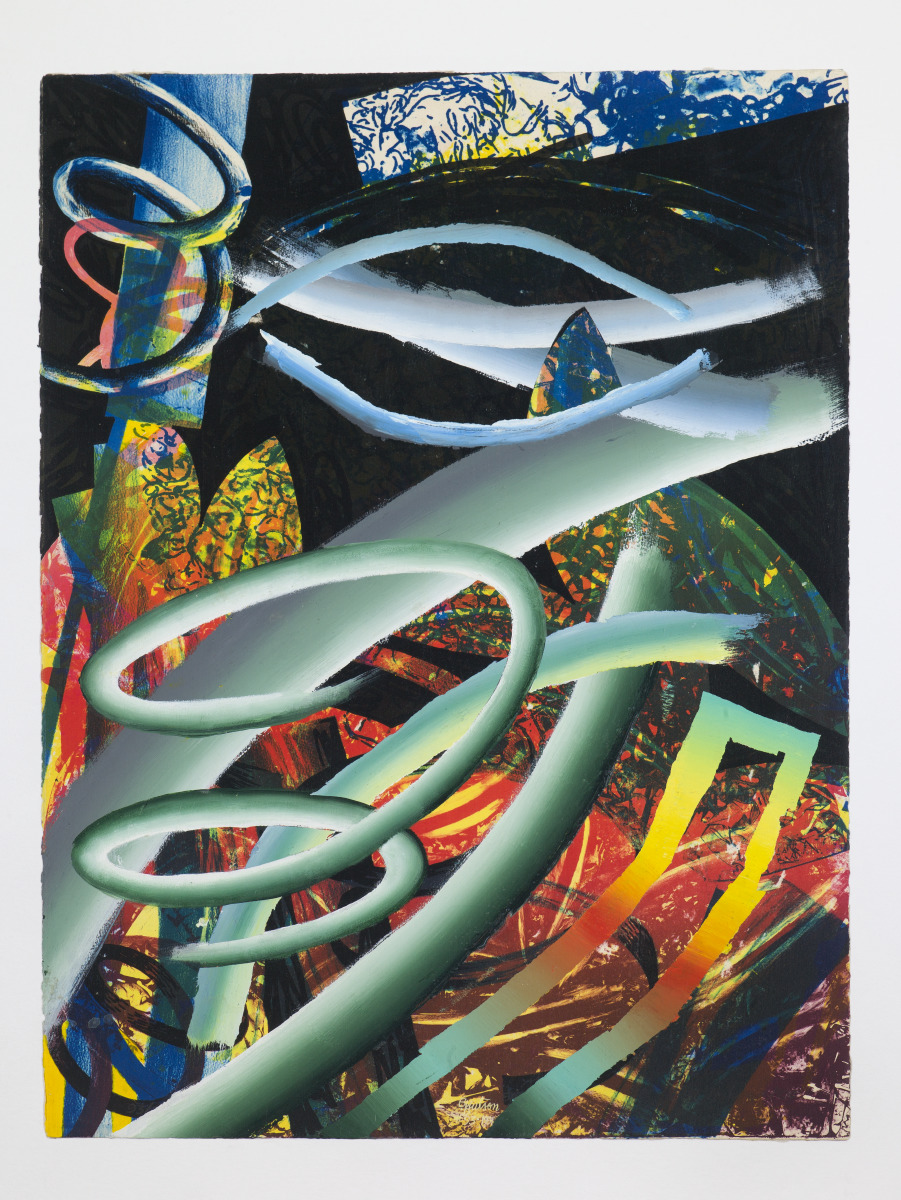

Many of the artists represented in the Ollie Collection emphasized experimentation with materials and processes in the studio. Rather than following prescribed modes of abstraction, they created works that combined techniques borrowed from painting, drawing, printmaking, collage, and sculpture.

The invention of acrylic paint, introduced to the commercial market in the 1960s, was an influential development. Numerous artists, including Frank Bowling, Bill Hutson, and Frank Wimberley, made this quick-drying medium a central part of their creative practices. Alternatively, others were inspired by ancient techniques, such as James Little’s adaption of encaustic painting.

These artists employed new methods of art making using nontraditional materials such as sticks or brooms to apply color and exploring unconventional processes such as dripping, staining, pouring, and weaving. Collage also allowed for a hybrid format, combining formal theories with the influence of quilting. Some artists developed systems to streamline their processes. For example, Frank Bowling created a floor platform and specialized stretcher to guide the flow of paint. This constant experimentation remains a critical concern driving these artist’s creative approaches.

Frank Bowling, British, born Guyana, 1936; Fishes, Wishes, and Star Apple Blue, 1992; acrylic on canvas; 39 1/2 x 40 inches; The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 187:2017; © Frank Bowling

Ebco Na, 1990-91

Bill Hutson, American, born 1936

offset lithograph with acrylic

printed by Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 160:2017

© Bill Hutson

Moon Dust, 1994

Allie McGhee, American, born 1941

acrylic

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 173:2017

© Allie McGhee

Fishes, Wishes and Star Apple Blue, 1992

Frank Bowling, British (born Guyana), born 1936

acrylic on canvas

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 187:2017

© Frank Bowling

Siempre (Always), 1998

Frank Wimberley, American, born 1926

collage of cut painted paper with pastel; 22 1/4 × 27 1/8 inches

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 184:2017

© Frank Wimberley

Study for Surrogate, 2002

James Little, American, born 1952

watercolor

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 168:2017

© June Kelly Gallery / James Little

Double Exposure, 2008

James Little, American, born 1952

oil and wax on canvas

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 190:2017

© June Kelly Gallery/James Little

Slightly Off Keel #60, 1999

Nanette Carter, American, born 1954

oil on Mylar

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 124:2017

© Nanette Carter

Untitled, 2014

Chakaia Booker, American, born 1953

woodcut and lithograph with chine collé

published by James E. Lewis Museum of Art Foundation, Inc., Baltimore

printed by Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, New York

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 122:2017

© Chakaia Booker

Journey Signs, 1993

Frank Wimberley, American, born 1926

acrylic on canvas with collage

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 194:2017

© Frank Wimberley

Rock Steady, 1992

Alonzo Davis, American, born 1942

mixed media

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 134:2017

© Alonzo Davis

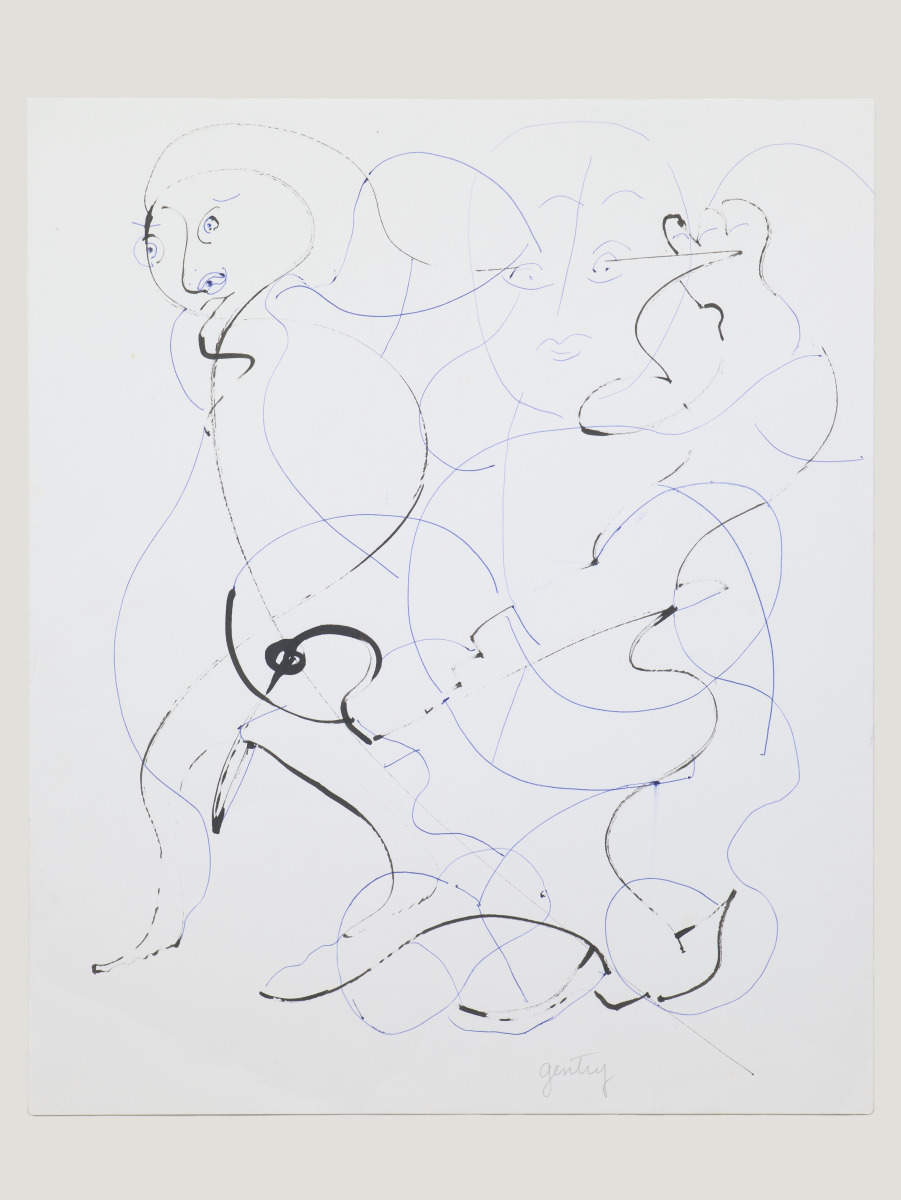

Although depicting the human form may seem contradictory to modern abstraction, figural representation has a long, intertwined history with the development of abstraction during the 20th century. Indeed, many artists enjoyed exploring the tension between the naturalistic portrayal of the figure or landscape and a purely abstract vocabulary.

Abstract art was a contentious topic in the black art community during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The Black Arts movement—the aesthetic counterpart to the Black Power movement—advocated that these artists create empowering images of subjects that directly communicated the shared experiences and heritage of their people. According to the Black Arts movement, abstract art largely failed to meet this charge, and, as a result, the movement criticized many who focused on harnessing the potential of color, line, and shape alone.

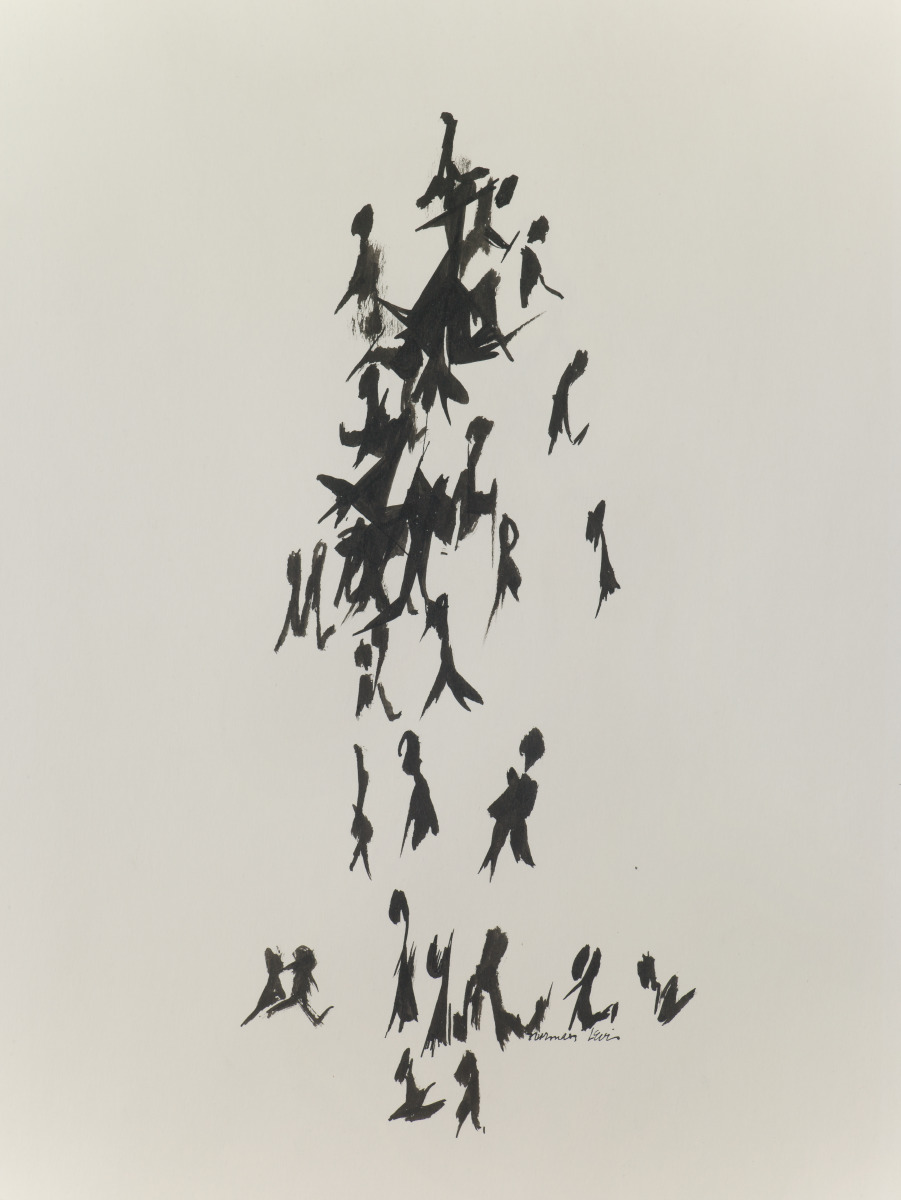

For committed abstractionists, Norman Lewis, who articulated his own activism through a combination of abstraction and figuration, often stood as a beacon. From an older generation, Lewis and Herbert Gentry retained the figure to create a dialogue with the automatic, gestural approaches of Abstract Expressionism. The younger Benny Andrews and William T. Williams tapped Surrealist, or dreamlike, imagery and geometric tendencies, respectively.

Herbert Gentry, American, 1919–2003; Our Web, 1990; gouache; sheet: 29 1/2 × 22 1/4 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 151:2017; © Mary Anne Rose and the Estate of Herbert Gentry

Our Web, 1990

Herbert Gentry, American, 1919–2003

gouache

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 151:2017

© Mary Anne Rose and the Estate of Herbert Gentry

Our Talk, c.1989

Herbert Gentry, American, 1919–2003

gouache

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 152:2017

© Mary Anne Rose and the Estate of Herbert Gentry

Untitled, 1966

Norman Lewis, American, 1909–1979

oil

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 167:2017

© The Estate of Norman W. Lewis; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Untitled, c.1940s

Norman Lewis, American, 1909–1979

ink

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 166:2017

© The Estate of Norman W. Lewis; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Togetherness, 1973

Norman Lewis, American, 1909–1979

etching

printed by Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, New York

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 164:2017

© The Estate of Norman W. Lewis; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Untitled No. 02 038, 2002

Lamerol A. Gatewood, American, born 1954

oil

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 135:2017

© Lamerol A. Gatewood 5.13.2002

Black Bird, 1980

Benny Andrews, American, 1930–2006

lithograph

printed by Springraphics, New York

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 117:2017

© Benny Andrews / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY

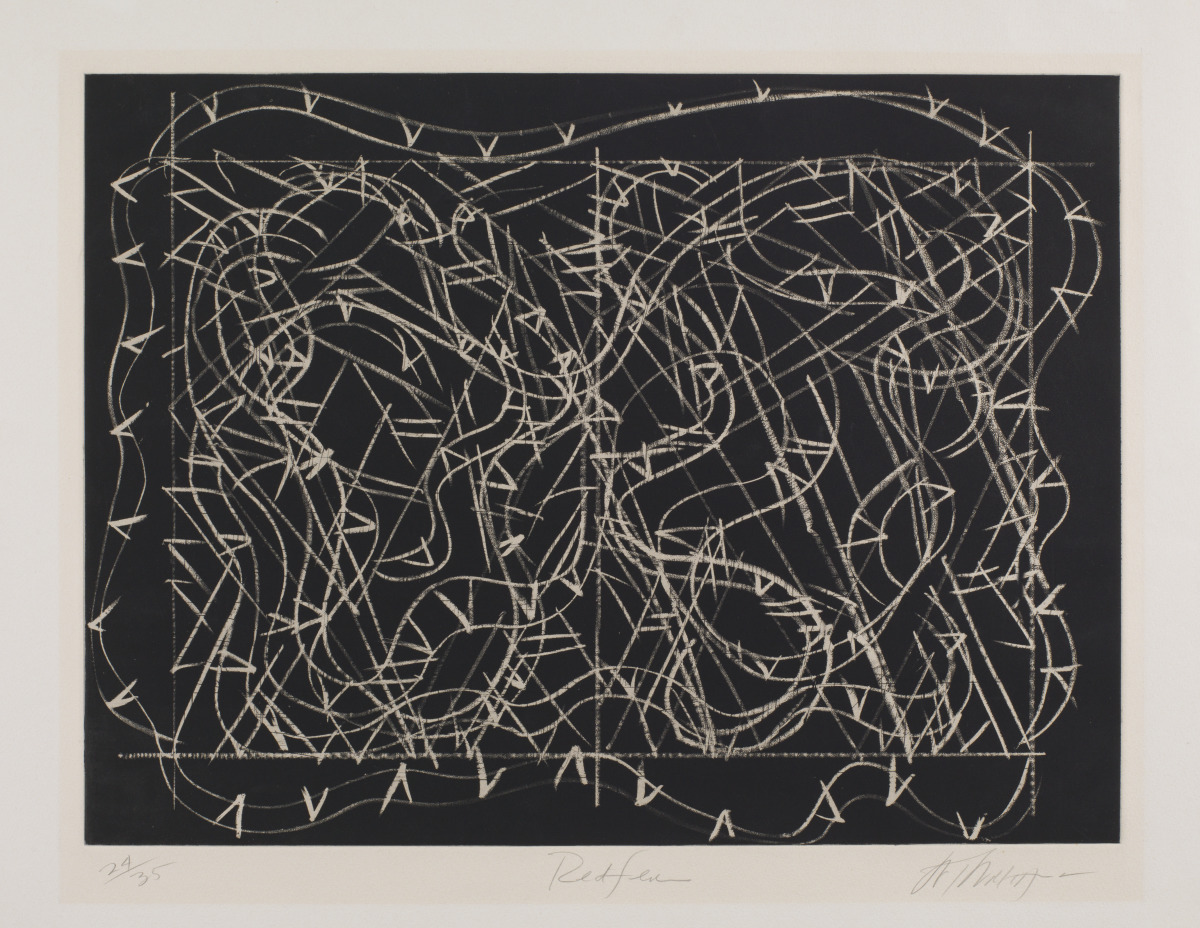

Red Fern, 1979

William T. Williams, American, born 1942

etching and aquatint

printed by Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, New York

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 182:2017

© William T. Williams; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

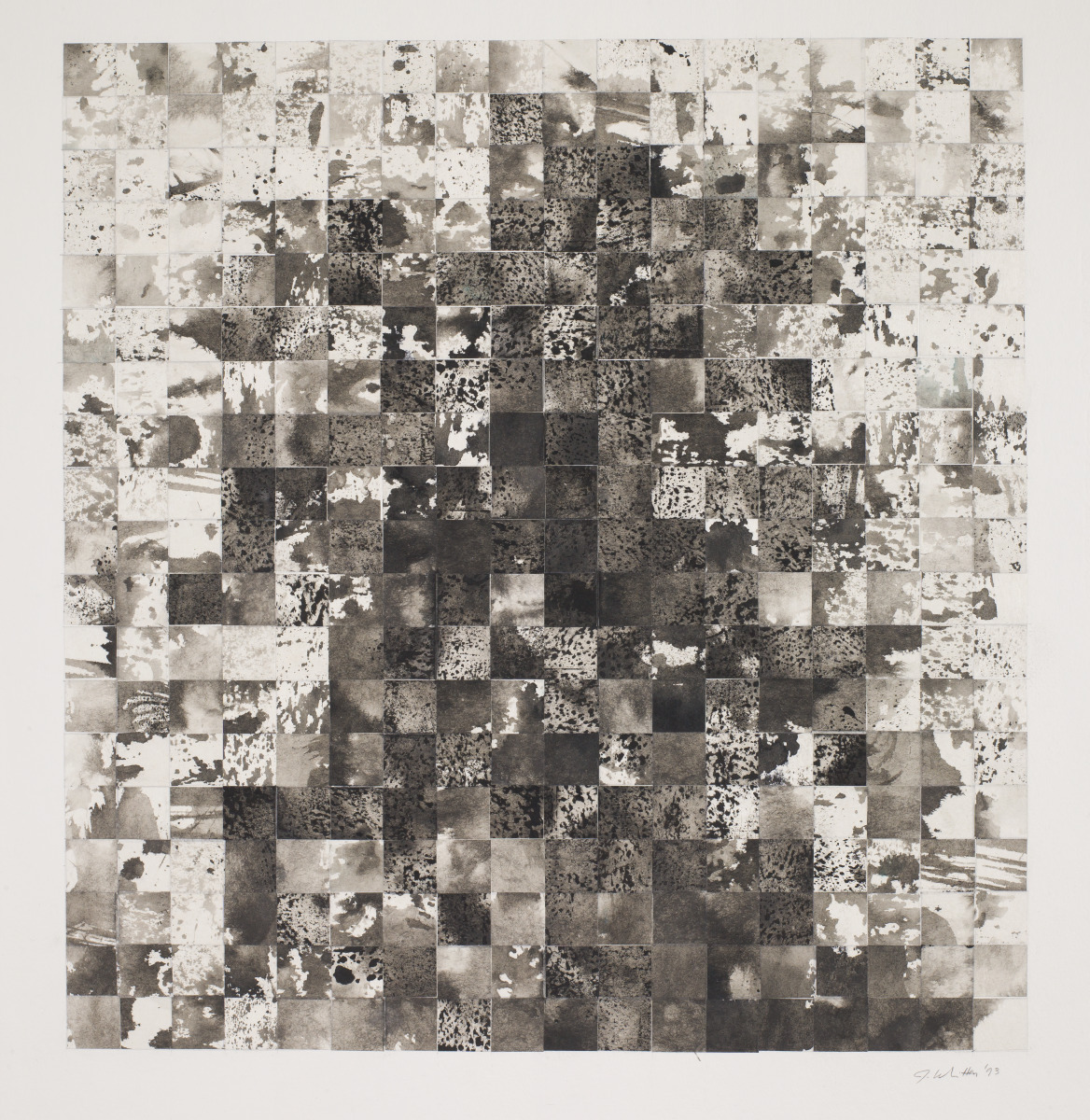

Self Portrait, 1993

Jack Whitten, American, 1939–2018

collage of cut painted paper

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 181:2017

© Jack Whitten Estate. Courtesy the Jack Whitten Estate and Hauser & Wirth

Many artists defining abstraction during the late 20th century made shape the subject of their art. These explorations, combined with concerns for color and materials, manifested myriad visual outcomes, from amorphous, fluid fields to crisply defined geometric designs. Moreover, artists’ considerations of shape played a vital role in the reassessment of painting during the 1950s and 1960s, when the medium’s definition fell under intense scrutiny.

Figures such as Ed Clark, Al Loving, and Sam Gilliam saw the medium as something more than a picture window into an illusionistic space. Thus, they refuted the rectangular canvas and instead configured their supports into rounds, hexagons, notched polygons, and even draped masses.

Ed Clark, who is credited with one of the earliest shaped-canvas paintings, observed: “I began to feel something was wrong. Our eyes don’t see in rectangles. I was interested in expanding image, and the best way to expand an image is in the oval or ellipse.” Recalibrating categories, these artists emphasized the sculptural qualities of painting, as well as drawing and prints, inspiring multimedia and installation artists who followed them.

Sam Gilliam, American, born 1933; Half Circle Red, 1975; acrylic on canvas; 78 x 33 x 6 inches; The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 189:2017a,b; © Sam Gilliam / David Kordansky Gallery

Untitled, 1968

Ed Clark, American, born 1926

acrylic

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 125:2017

© Ed Clark / Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

Mercer Street series VI, 1986

Al Loving, American, 1935–2005

collage of painted and printed papers

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 171:2017

© Al Loving

Half Circle Red, 1975

Sam Gilliam, American, born 1933

acrylic on canvas

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 189:2017a,b

© Sam Gilliam / David Kordansky Gallery

Life and Continual Growth, 1988

Al Loving, American, 1935–2005

collage of cut printed paper with acrylic

printed by Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 170:2017

© Al Loving

Zayamaca #4, 1993

Al Loving, American, 1935–2005

collage of painted paper mounted on Plexiglas

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 172:2017

Courtesy the Estate of Al Loving and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York © Al Loving

Ruby and Ossie, 2000

Sam Gilliam, American, born 1933

acrylic on plywood with metal hardware

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 188:2017

© Sam Gilliam / David Kordansky Gallery

Golden Neck, 1993-94

Sam Gilliam, American, born 1933

screenprint, offset lithograph, and hand applied acrylic, with stitching

published and printed by Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 154:2017

© Sam Gilliam / David Kordansky Gallery

Untitled, 1969

Ed Clark, American, born 1926

acrylic and dry pigment

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 126:2017

© Ed Clark / Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

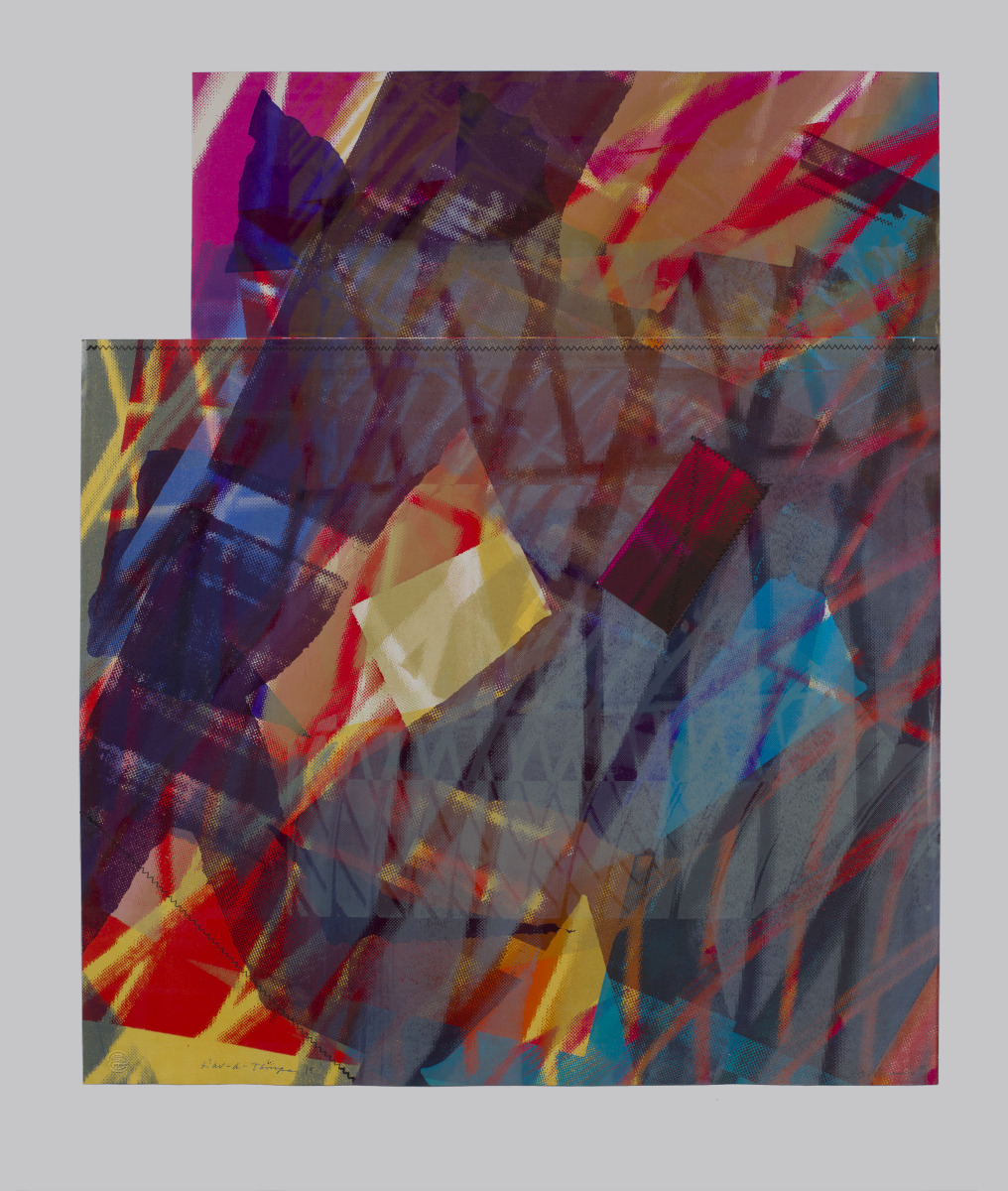

Hav-a-Tampa “15”, 1995

Sam Gilliam, American, born 1933

screenprint and monoprint, with stitching

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 155:2017

© Sam Gilliam / David Kordansky Gallery

Meditation in Blue, 1998

Ellsworth Ausby, American, 1942–2011

acrylic

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 118:2017

© Ellsworth Ausby

Untitled, 1979

Terry Adkins, American, 1953–2014

pastel and wet color

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 114:2017

© 2019 The Estate of Terry Adkins / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

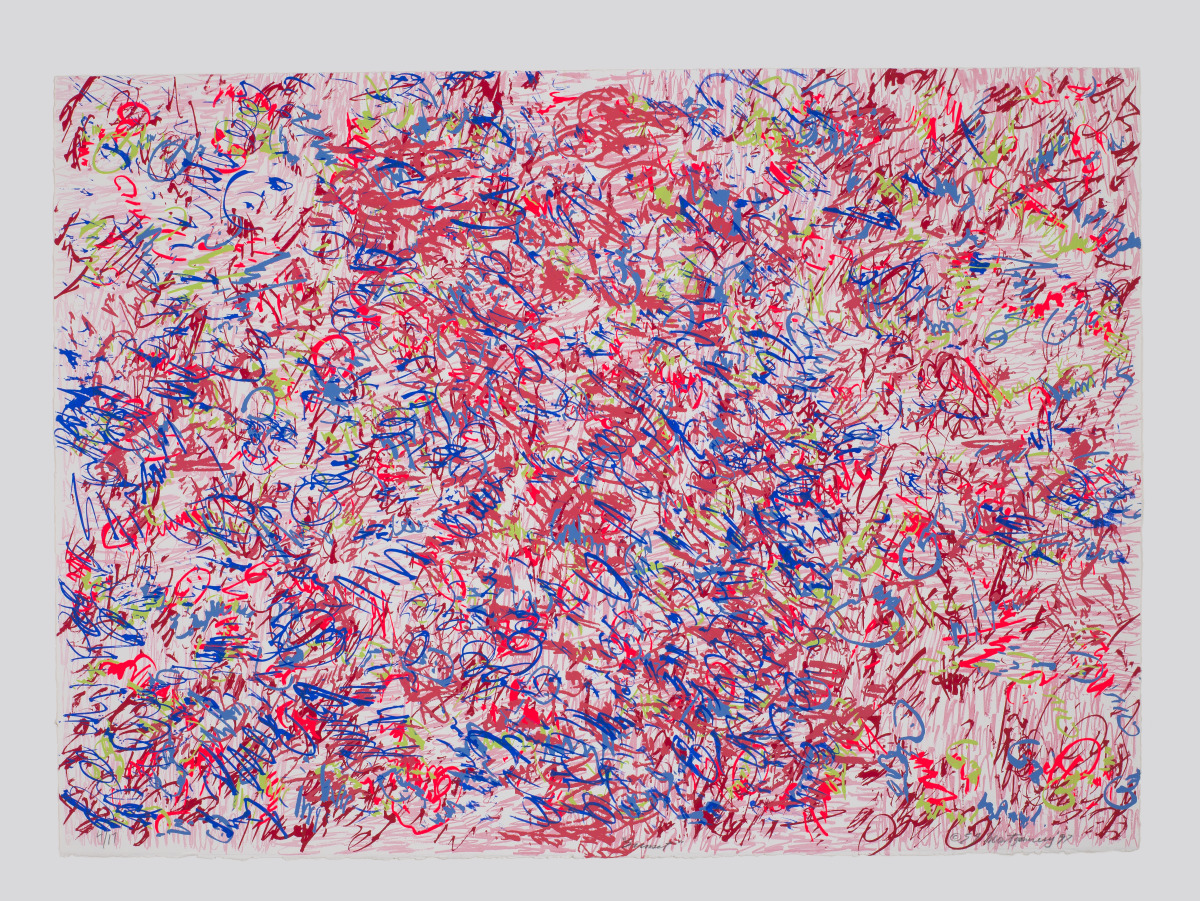

City Lights (Prophet with No Tongue), 1988

City Lights (Prophet with No Tongue), 1988

Mary Lovelace O’Neal, American, born 1942

offset lithograph and screenprint

The Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection, Gift of Ronald and Monique Ollie 177:2017

© Mary Lovelace O’Neal

by Quincy Troupe

the shape of abstraction is what the mind believes

it sees, figures, colors emerging from a canvas

(or a block of steel, limestone, wood chipped & cut,

chiseled, shaped into a memory, sanded down,

refined into grace, polished to a high sheen, almost

a mirror, reflects a creative imagination, where

the artist leaves their heart inside a language

born from power of a hammer’s head, artistry evolves

from there, fertile dreams of makers are transferred

in boogie-woogie riffs from bebop, deep in delta blues,

live inside a clean womb, hard surfaces birthing faces,

where voices scat, rap over hot jazz licks in harlem, zing

original forms, create words—like razzmatatazz—sling them

sluicing colors into living language—whatever raises to life

& sings, shocks, or disgraces the senses—as long as we are

here in the world, if it doesn’t burn, or explode into wars

created by man-made nuclear infernos—when horror,

conflict is chosen over beauty—a brushstroke can evoke

memory as love, heard sometimes in whispers),

is what a painter’s brushstrokes bring to life from empty

blank white wombs of canvases—they could be red, brown,

black, tan, or yellow canvases—until unknown pulse beats

birth embryos from there, raise them into breathing forms

from deep inside creative impulses, splashed with colors,

tones, as when we look up at cloud formations & see

in the sky wonders, images created up there are their own

music, rhythm, as when the sea rolls in clapping waves

foaming, roaring, then snarling into what eye imagine

mad animals might hear when suffering with rabies,

on the other hand eye imagine eyeballs bulging to see

what a ship way out on the infinite, razor-sharp blade edge

slicing the sea in half might mean from our view here on shore,

on a gray day full of silhouettes, contours of waving figures,

outlines of fluctuating images, forms dissipating

inside exhaust gasses belching from a smokestack vessel’s

burner trailing shapes behind it as it sails eastward

toward some unknown port it will reach in the dark dead

moment right before midnight, a star shining bright high

above in the night, is a white echo of light showing the way,

or is a one-eyed cyclops blinking down from history,

they are paintings after all, disintegrating on that blue

grey canvas of sky, is a rorschach test of faith, of what

one thinks the eye recognizes as art, transfers back to

probe the brain in an instant of volatility—which

is the push & pull of capricious decision-making

filled with impulsive hints of what or what not to choose

when eyeing creative choices offered up as barter,

in exchange for banknotes, trade, switch or swap,

is a form of negotiation, is a haggling bargain point,

which is an art form of sorts too, though not the same

creative level of expression true art springs from—

because art is shrouded inside mystery & magic

it is a force that can enrich, sustain life,

nourishing through beauty, joy, mirroring truth,

questioning what we know of ourselves, or don’t know,

asking us questions—why are we here & where

will all these shapes take us to through colors splashed

with beauty—or shock—where music evokes lines

tap-dancing through forms, breaks into rhythms,

takes us to a place where imagination wanders,

fills up space with magical, mysterious wonder