The idea of a portraitist at work, standing behind canvas or camera to create an image of their subject, might seem entirely unrelated to an industrialized assembly line. But portraiture can also be considered an industry because its producers create a closely related set of goods.

In the 1600s colonists brought European conventions of portraiture with them to North America, where they took root. As Missouri towns expanded during the 1800s, so too did the portraiture industry. Artists traveled to the region to meet the population’s growing demand for images of themselves that would demonstrate their social, economic, and familial ambitions.

By the 1840s photography began to expand portraiture’s conventions and expectations. Today contemporary artists continue to challenge the fundamentals of portraiture: who is portrayed, why, and how.

Looking Prompts

Spend time looking at each of these photographs.

- What do you notice about the facial expressions in each of the photographs?

- What do you notice about the poses of the people in the photographs?

- What else do you notice as you compare these photographs?

- What clues do you see in the photographs that might help you discover a bit more about these people?

- Imagine if two or more of the people portrayed in these images were to meet. What do you imagine they might talk about? What do you imagine they might do next, after they met? Write a short story about their meeting.

-

About these Artworks

The most significant change to the portrait industry came with the arrival of photography in the 1840s. The medium’s most important early practitioner in the confluence region was Thomas Martin Easterly, who specialized in daguerreotypes, which are one-of-a-kind images created without negatives on silvered surfaces. Faster to make, less expensive to purchase, and more accurate than a painted portrait, daguerreotypes changed expectations of and access to portraiture and offered more opportunities for commercial production.

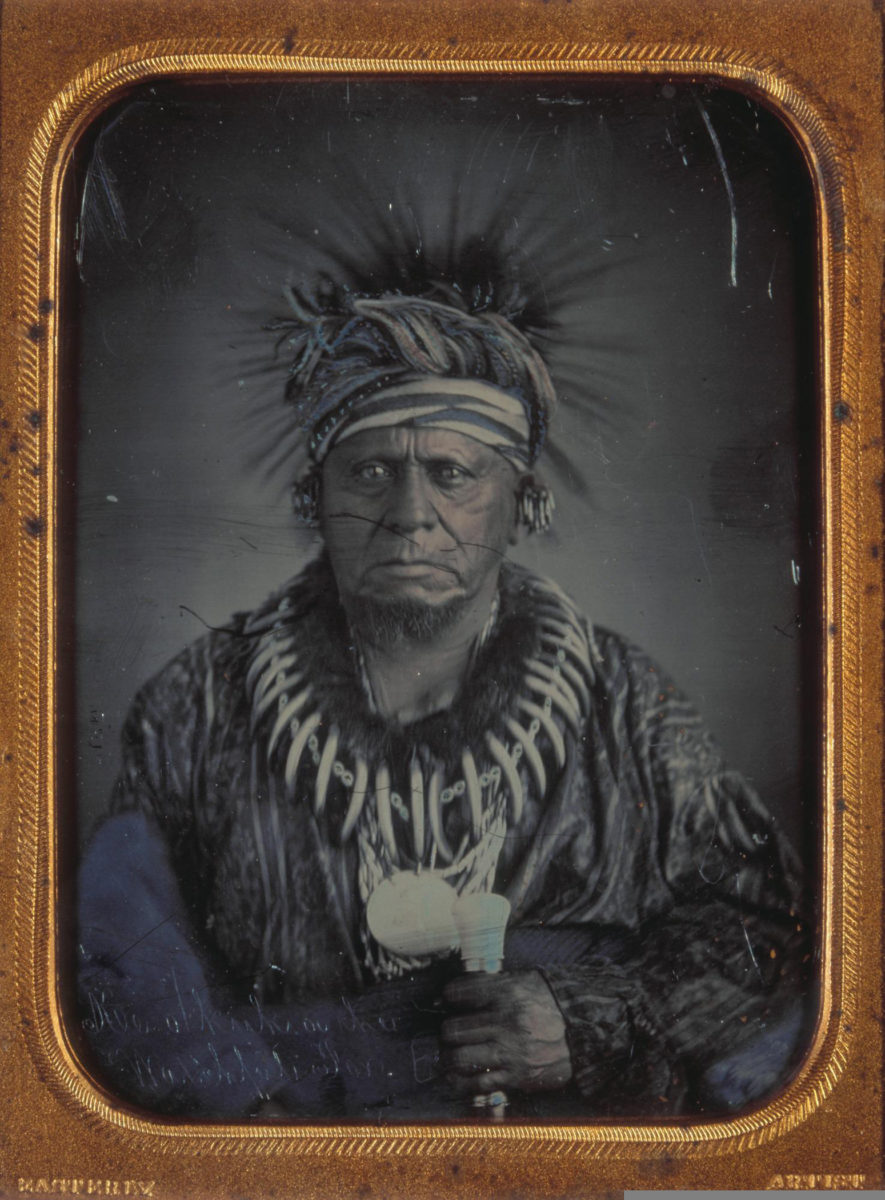

Easterly created a collective portrait of the confluence region through his daguerreotypes. Easterly’s camera recorded the candid expressions of 100s of St. Louis residents and visitors, such as a little boy’s scowl or a man’s furrowed brow. His psychologically penetrating portrait of the Sauk and Fox leader Keokuk is considered the first photographic portrait of a Native American.

Easterly also photographed the area’s African American residents, such as Robert J. Wilkinson. Many may have agreed with American abolitionist Frederick Douglass that the “democratic art” of photography allowed African Americans to appear as individuals rather than as reductive stereotypes.

-

Listen to learn more about these works of art.

Audio guide for Art Along the Rivers: A Bicentennial Celebration

-

Image Captions

(top left): Thomas M. Easterly, American, 1809–1882; Keokuk, or the Watchful Fox, 1847; hand-colored daguerreotype; 5 x 4 inches; Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis 2021.54

(top right): Thomas M. Easterly, American, 1809–1882; Unidentified Mother and Small Son, c.1850; hand-colored daguerreotype; 4 x 3 1/2 inches; Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis 2021.57

(bottom left): Thomas M. Easterly, American, 1809–1882; Robert J. Wilkinson, Barber of the Southern Hotel, c.1860; daguerreotype; 4 x 3 1/2 inches; Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis 2021.56

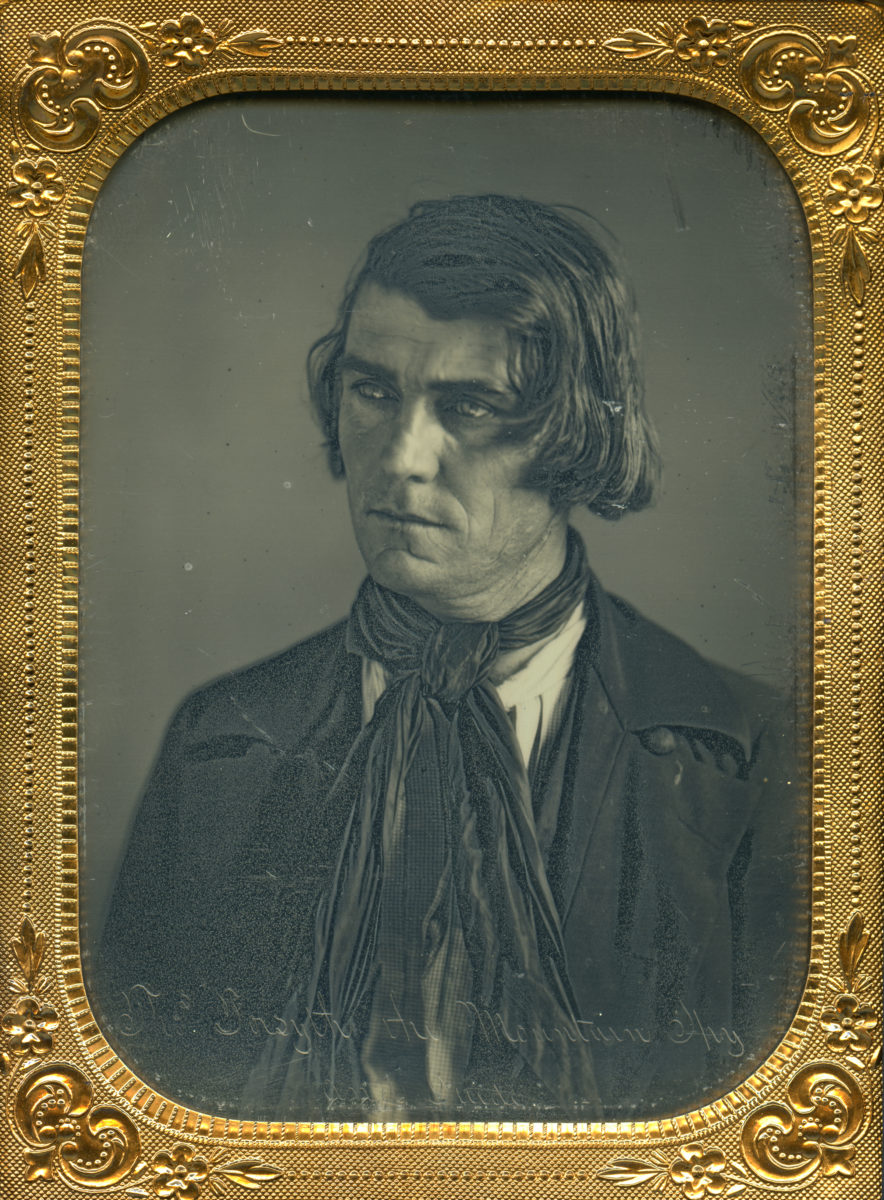

(bottom right): Thomas M. Easterly, American, 1809–1882; Thomas Forsyth, Mountain Spy and Guide, 1847; daguerreotype; 5 x 4 inches; Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis 2021.55