How do artists and works of art advocate for political, social, or environmental viewpoints?

Section Overview

Artworks in this section advocate by drawing attention to politics, people, and places. Some have communicated support for political policies or promoted recognition of people from marginalized groups. Others have countered social injustices or investigated relationships between humans and nature. All speak boldly in the hopes of effecting change.

In this section you will find an overview, thematic discussion questions, selected artworks that advocate in some way, looking prompts, information about the artwork, and discussion questions related to each artwork. At the end of this page you will also find connection activities that apply to multiple subject areas, a looking guide containing images of the artworks that may be used in class settings, relevant standards connections, and a slide presentation with artwork images and questions for discussion.

Art as Advocate Introductory Video

Art as Advocate Introductory Text

Many events central to the history of the United States occurred in the confluence region. St. Louis is among America’s cities whose residents have advocated most fiercely for social and political change. Some of the area’s pivotal incidents have national significance, such as the 1820 Missouri Compromise and the 1847 initial decision in the Dred Scott case.

The region also saw the Civil War’s first general emancipation in 1861, the nation’s first general strike in 1877, and some of the most radical labor politics and demonstrations in the 1930s. More recent activism has addressed the continued destructive inequities of racism, including turbulent clashes in Cairo, Illinois, in the 1960s and the intensification of the Black Lives Matter movement following the 2014 fatal shooting of Michael Brown Jr. in Ferguson, Missouri.

Key Terms

Advocacy

Public support or recommendation of a cause, policy, or reform

Activism

Efforts to create, inspire, promote, or direct social, political, economic, or environmental reform toward a perceived greater good; taking intentional actions to bring about change

Abolitionist

An individual who favors the end of a practice or institution, primarily used in reference to abolishing slavery

BIPOC

Black, Indigenous, and People of Color

Earthwork

A work of art or structure created from the land itself using natural materials such as soil and rocks

Mural

A large-scale work of art, usually a painting on a wall, street, or public venue

Social Justice

Equity in the distribution of economic, social, and political rights, privileges, and opportunities

Questions for Discussion

- How can artwork accomplish a goal, solve a problem, or make a statement?

- In what ways do artists advocate through art?

- How do artists and objects advocate for political, social, or environmental viewpoints?

- What is the relationship between art and activism? In what ways can you creatively advocate for change?

Selected Artworks

Looking Prompts

- Imagine you are sitting or standing on the raft with the people pictured. Where would you like to be on the raft? What might you see if you look in different directions? What do you imagine it would feel like to be on the raft?

- Now imagine you are on the end of the raft facing the people we see in the painting. Explore with your senses.

- What do you see?

- What can you hear?

- What do you smell?

- What does the weather feel like on your skin?

- As you gaze across the flat surface of the water, what do you notice?

As a follow-up to the questions above, ask, What do you see that makes you say that?

- If you could ask any of the people in this scene a question, who would you ask and what would you ask them?

-

About this Artwork

While at first glance this appears to be an idyllic river scene, dangers lurk in the background. A sandbar lies menacingly to the left, and a snag, or fallen tree, punctures the river’s surface to the right. Both features were capable of wrecking rafts and steamboats alike, serious impediments to the future of commerce on both the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers.

George Caleb Bingham was primarily a self-taught artist who spent much of his childhood in Franklin, Missouri. Fascinated by people and places along Missouri’s rivers, Bingham captured many scenes of river life in the later half of the 1800s. Both an artist and a politician, he often used his paintings to lobby for commerce and investment in his home state.

Raftsmen Playing Cards depicts a quiet moment of leisure among six raftsmen aboard a simple raft. The raftsmen had the job of transporting goods from sites of production to commerce destinations via rivers such as the Mississippi and Missouri. Exhibited first in St. Louis and then in New York City in 1847, Raftsmen Playing Cards conveyed two messages. One was directed mostly to its national audience: in sharp contrast to the typical image of river laborers, who were frequently portrayed as vulgar, violent characters, Bingham’s raftsmen appear clean and collegial—civilized folks who could be trusted to uphold the pursuits of the nation.

Raftsmen Playing Cards also participated in a national debate central to Missouri politics at the time. Throughout the 1840s Bingham and other Whig politicians advocated for the federal government to fund the cleanup of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers as part of their desire to integrate Missouri more fully into the national economy. As this vision relied on rivers to move goods from their places of production in the West to their markets in the East, any threat to river commerce took on outsize importance. In Raftsmen Playing Cards Bingham demonstrated a principal impediment to navigation: trees that have toppled from the sandy banks into the river lodge in its bottom, creating large snags, seen at the right of the painting. In showcasing these snags and other dangers on a national scale, Raftsmen Playing Cards advocated for the cleanup of these rivers with federal funds.

In 1847 Bingham exhibited a second painting, Lighter Relieving a Steamboat Aground, showing the result of such obstructions: a steamboat has wrecked on a sandbar, necessitating the rescue of its passengers and cargo. Together, these two paintings offer a pointed rebuke to critics of federal intervention—such as President James Polk, who had repeatedly vetoed a bill to clear the rivers—by showing the results of their inaction.

-

Questions for Discussion

- In what ways do you think the artist used this painting to advocate for river cleanup?

- Do you feel that the artist was successful in conveying his message?

- In what way might you change or adapt the painting to make it even more effective?

- George Caleb Bingham highlighted one group of people who appreciated and benefited from the Mississippi River. Consider the social value of the river. Why would it be valuable to preserve these natural resources from social or cultural perspectives?

Looking Prompts

- What’s going on in this sculpture?

- What do you see that makes you say that?

- What more can you find?

- Consider each figure in the sculpture.

- What do you notice about their poses?

- How would you describe their facial expressions?

- What is one word you would use to describe their mood or emotion?

- What do you wonder about as you look at this sculpture?

-

About this Artwork

A family is about to be torn apart in a tragic outcome of chattel slavery, where human beings were denied agency and treated as property. The auctioneer’s hair curls into devil horns, revealing his evil character. This tabletop sculpture, an icon of the abolitionist cause, was created following John Rogers’s 18-month residence in Hannibal, Missouri, where he had worked from 1856 to 1857 as a master mechanic for the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad. As he expressed to his family of “rank abolitionists” in Massachusetts, “the curse of slavery is dreadfully apparent here.” While Rogers did not write about attending a slave auction in Missouri, such sales occurred with regularity in Hannibal and neighboring cities as part of the national slave-trading network. Rogers’s first and only experience of living in a state where slavery was legal brought about a new consciousness; as he remarked during his residence in Missouri, in reference to President Franklin Pierce’s opposition to the abolitionist movement: “I am not much of a politician—I never was. . . . But I begin to see how things really are now.” The Slave Auction “touched the conscience of a nation,” as a critic later wrote, and became an abolitionist icon due to its display in the office of the National Anti-Slavery Association in New York City and its frequent reproductions in the abolitionist press.

-

Questions for Discussion

- In what ways can art draw attention to an issue?

- What contemporary connections can you make to The Slave Auction?

- In what ways are contemporary artists utilizing the arts to “touch the conscience of the nation”?

Looking Prompts

- What do you see as you look at this photograph?

- What do you think about that?

- What does it make you wonder about?

-

About this Artwork

Two men sit below painted portraits of Black leaders. This photograph documents one of St. Louis’s most important community-based art projects: a three-story mural created in 1968 by volunteers from local civil rights groups.

In 1967 a mural celebrating African American achievement, known as The Wall of Respect, was painted in Chicago, sparking a nationwide movement of similar urban murals that powerfully demonstrate how art can advocate for its communities. By 1975 the Chicago mural had inspired more than 1,000 murals across the United States, primarily painted by BIPOC artists.

In 1968 volunteers from St. Louis civil rights groups joined together to paint a Wall of Respect on a three-story building at 2800 Franklin Avenue, near the Pruitt-Igoe housing project and the headquarters of the Black Artists’ Group. Photographer Ken Light documented the wall in 1971.

Organized by Luther Mitchell and painted by Leroy White, Walter Friday, and five other artists whose names we have yet to identify, the wall was intended to “bring on Black awareness and Black consciousness of Black history,” as one community leader announced. It memorialized 16 Black leaders, 7 of whom—Ray Charles, James Baldwin, Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable, LeRoi Jones, Frederick Douglass, W. E. B. Du Bois, and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King—are pictured in Light’s photograph alongside a version of Marcus Garvey’s exhortation, “Up, you mighty race.” On other parts of the mural not visible in Light’s photograph, there were portraits of Phyllis Wheatley, Muhammad Ali, and St. Louisan Dick Gregory, among others. The wall quickly became, in the words of one supporter, “a gathering place for meetings and performances” and “a symbol of Black achievement and determination.” In Light’s photograph two Black individuals sit in the midst of these heroes, suggesting they also embody Black excellence. But the mural also became a target: it was vandalized at least twice, once just weeks after its creation and again in January 1969. The artists later returned to the wall and restored elements of the portraits that had been defaced. The photograph documents the four-year-old mural scarred by this hatred, with white paint defacing several portraits. Despite such acts, the mural held a central place in its community for more than a decade before the building on which it was painted fell into disrepair and was demolished. For poet Eugene Redmond, The Wall of Respect was “Built so Blacks can see their (Blackness) tower.”

-

Questions for Discussion

- This mural was painted on the side of a building in St. Louis. Where else do you see murals?

- What would be important to think about when choosing a site for a mural?

- Why would an artist choose to paint a mural in a public space rather than in a gallery or other art institution?

- In 2011 artist Grace McCammond collaborated with youth from Herbert Hoover Boys and Girls Club to paint The St. Louis Wall of Fame mural on the side of Gramophone, a business located in the Grove neighborhood of St. Louis. Compare this mural with Ken Light’s image of The Wall of Respect.

- Consider the following questions:

- What might the artists’ goals be in painting these murals?

- Why is one still on view and not the other?

- How might these goals align with or differ from those of the community in which each mural is located?

- Additional Resources

Looking Prompts

- Look closely at this work of art. What do you discover as you look? Write a list of 10 nouns or adjectives that describe what you see.

- What details emerge as you continue to look?

- How would the impact of this image change if it were very small? If it were very large?

- What if you were to change the background?

- What else do you notice about the composition of this image?

-

About this Artwork

What do hands and their gestures reveal?

This image of hands originated during the protests after Michael Brown Jr. was shot and killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, 2014. Artist Damon Davis, an active member of the Ferguson protest movements, chose seven fellow protesters from diverse backgrounds as his subjects. He photographed just their hands, held up in a gesture that echoes the phrase “hands up, don’t shoot,” heard throughout the uprisings. By titling the project All Hands on Deck, however, Davis transformed a gesture of surrender into one of solidarity, community, and, above all, a call for change.

The photographs were originally printed in large scale and pasted onto boarded-up storefronts during the Ferguson protests. In Davis’s own words: “The project in itself was a protest to change the physical space of the street in the aftermath of the murder of Michael Brown. The boarded-up buildings created a narrative of destruction before anything had even happened, and that fed into the media’s biased portrayal of the protesters. It was a way to weaponize art to create a counternarrative centered on the unity and love I saw every time I went out to protest. It sought to raise the morale of the protest community to continue the long fight.” The print in this resource is part of a series of lithographs created from Davis’s photographs, which were published in a limited edition by Wildwood Press in St. Louis.

Davis’s multidisciplinary practice spans film, music, sculpture, photography, and print media. According to Davis: “My work is rooted in the Black American experience because that is my experience. I am motivated by how I internally process the idea of race and how it has personally affected my life as well as the larger sociopolitical implications of race in America and the world.”

-

Questions for Discussion

- Consider the question raised at the beginning of the About this Artwork section above: What do hands and their gestures reveal?

- What can we learn about an individual’s story from their hands?

Looking Prompts

- Before reading any information about this artwork, look closely at the image. If you were the artist, what title would you give it? What about it makes you choose that title?

- If you were asked to choose a song to go along with this image, what would you choose?

- What more can you find as you look at this image?

-

About this Artwork

Times Beach, Missouri, suffered one of the nation’s largest environmental disasters. Located about 17 miles southwest of St. Louis along the Meramec River, the town of Times Beach was founded in 1925 as a weekend resort community, and by the 1970s it was home to about 2,500 year-round residents. In 1982 the town was declared uninhabitable after a contractor sprayed the town’s roads with the toxic chemical dioxin to suppress dust. Following its designation as an Environmental Protection Agency Superfund Site, it was entirely evacuated by 1985.

Emmett Gowin included the site in a series of aerial photographs that recorded places where humans have radically altered landscapes, including nuclear test sites, missile silos, coal mines, and more. The Abandoned and Condemned Village of Times Beach, Missouri, which looks east into the early morning light, appears peaceful and serene. Lush foliage and a tidy grid of streets betray no trace of the toxic chemicals lurking there. Following the evacuation, the land appears to be returning to nature. The photograph seems to exemplify Gowin’s astonishment that, as he described: “in spite of all we have done, the earth still offers back so much beauty, so much sustenance. So much of what we need is embodied in it.” For him, such pictures became “an opening through which to seek what we don’t know or already know and should take seriously.” In the case of Times Beach, this responsibility means attending to both the careful management of hazardous materials and the ongoing physical, psychological, social, and economic impacts on its former residents.

-

Questions for Discussion

- In what ways does learning the story of Times Beach change how you think about Emmet Gowin’s photograph?

- What makes this image successful or not successful as a tool to advocate for environmental concerns?

-

Additional Connections

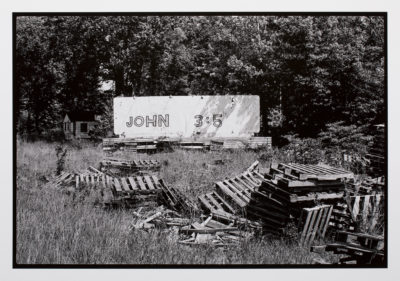

Sam Fentress, American, born 1955; Times Beach, Missouri, 1986, printed 2020; gelatin silver print; image: 7 7/8 x 11 3/8 inches, sheet: 11 x 14 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of Sam and Betsy Fentress 59:2021; photo © Sam Fentress

Sam Fentress’s photograph records the pallets left behind in Times Beach. It is part of a project examining the placement of Christian signs in the landscape. The billboard’s biblical verse references baptism, a ritual of purification by water—a pointed juxtaposition for a place so contaminated by liquids.

Listen to this audio guide stop to learn more about Times Beach.

Looking Prompts

- Compare these three images. What is similar about each of the landscapes? What is different?

- If you could choose one of these images to teleport into, which one would you choose?

- What caused you to choose that one?

- Where would you want to land in the image?

- What would you want to have with you if you were in this landscape?

-

About these Artworks

Three mounds dominate these photographs. St. Louis was once nicknamed Mound City for the numerous ancient Mississippian earthworks that dotted its landscape. The priorities of urban and industrial development resulted in the demolition of most of these mounds. For instance, construction for the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair razed those that were located where this Museum now stands.

In the last century landfills and slag heaps have become mounds of modern times. In an ongoing project, photographer Jennifer Colten and writer Jesse Vogler engage with ancient and contemporary mounds in the American Bottom, located in the Mississippi River floodplain. As Vogler describes:

“The American Bottom floodplain that lies to the east of St. Louis is rightly celebrated as the center of a vast pre-European civilization that had as its central architectural and landscape expression the construction of earthen mounds. Mound complexes from the well-known Cahokia Mounds to the lesser-known Big Mound and Grassy Lake sites remain the defining traces of a long and advanced era of North American settlement. By most archaeological accounts this constellation of mounds marks the largest urban center north of Mexico—with the apex of Native American mound building in the region spanning the years between 800 and 1100 CE.

”Yet the construction of mounds continues. Mound building has, if anything, even increased. While the civic and cosmic ordering that animated so much of the Mississippian-era mound builders has, in this new era of mound building, been sidelined for the logistical and the proximate, our contemporary mounds index a way of being no less profoundly than the artifacts of the mound builders of prehistory. Slag heaps, salt domes, aggregate piles, landfills, mulch mounds—these are the forms of our cosmologies.”

In bringing these ancient and contemporary landscapes into dialogue, Colten and Vogler ask us to question how individuals and communities have defined human interventions in the landscape as either significant or insignificant across time, and what these judgments reveal about the cultures that made them. Colten and Vogler propose that “each of these mounds, on its own terms, is both significant and insignificant,” because “in landscape, it all matters. It all has meaning.”

-

Questions for Discussion

- Compare these photographs with Emmet Gowin’s The Abandoned and Condemned Village of Times Beach, Missouri. Discuss how these projects advocate for awareness of environmental issues and human interventions.

- What role can/does photography play in social, environmental, or political advocacy? In what other ways might you use visual art and/or imagery to advocate for environmental concerns?

Art as Advocate Connection Activities

Consider and Respond

Shortly after being painted, The Wall of Respect was vandalized when white paint was splattered across it. Several decades later, contemporary artist Faring Purth painted a mural in the Grove neighborhood of St. Louis. Before she was able to complete the mural, it was defaced. In response, she stated, “the power of art is that it can reveal something.” What do you think she meant by that? What is your view of her statement? Write an argument in support of or against this statement. Include examples to support your argument.

Create

Consider the different hands depicted in Damon Davis’s All Hands on Deck. Return to the question posed in the About the Artwork section for Davis’s All Hands on Deck, What do hands and their gestures reveal? Spend some time drawing your own hand. Observe the details of your hand. What accessories are around your hand? What position is your hand in? How does the position change the meaning that is conveyed? Share and compare with a partner or in small groups.

Research

Research murals in St. Louis or another place near you. Explore some of the venues or themes that artists choose, or focus on a specific artist who paints multiple murals. Select a collection of murals that you found in your research and create a travel guide or map to help others find and learn about these murals. Include a combination of pictures and words to help tell the story of these murals and the city, town, or neighborhood where they have been painted.

Create

Create a mural in your classroom or hallway. Find a long piece of paper. Attach it to a wall or floor, or use chalk and create a mural outdoors. Work as a class to design your mural. Consider a theme or message for your mural. You may want to design an image together or create a design that allows each person to contribute individually (for example, several circles of varying sizes that can be filled in with different pictures). Using markers, paint, pencils, chalk, or other materials, draw and fill in your mural.

Advocate

How can you use art to advocate?

What is an environmental, social, or political issue that you are concerned about? This can be an issue that you have witnessed at your school, in your community, or even globally, such as climate change. Choose an issue that you would like to focus on. Research at the library, online, or in your community to learn more about the causes of this issue and potential resolutions. Develop a work of art that either addresses this issue or teaches others about it. A few ideas for art media include drawing a picture, designing a poster, creating a sticker or chalk campaign, taking photographs, making a book, or building a sculpture. Create a sketch of your idea to help plan your final project. Design and create your artwork.

View other artworks from the Saint Louis Art Museum collection and related websites for further inspiration on art and advocacy.

Research

Research an artist or event from this section that you would like to learn more about. Develop one to two questions to guide your research (for example, What has happened to Times Beach, Missouri, since it was evacuated in 1985? In what ways has the landscape changed or developed in response to the event?). Give a presentation or design a visual to share what you discovered with your class.

Create

A zine is a self-published booklet similar to a magazine. Zines have been used by many artists and activists to share information with audiences using do-it-yourself materials and techniques. Many zines are made by drawing or gluing elements onto a piece of paper and then using a photocopier to make multiple versions that can be folded into a booklet. To create a zine, begin by researching a bit about zines. Find a zine template you like, or create your own design. Then, working individually or in small groups, choose a theme or issue to focus your zine around. Incorporate writing, poetry, drawing, and magazine or newspaper cutouts related to your theme or issue. As you design your zine, consider what you want your audiences to learn or take away when they read it. Create multiple versions of your zine and share with your classmates. You might even want to collect all the zines together into a class library.

Research

Rivers, such as the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio, have shaped the confluence region that is described in this resource. These waterways enabled people, goods, art, and ideas to move around the region and the land that has become the United States. In paintings such as Raftsmen Playing Cards, George Caleb Bingham explored life on and along such rivers.

Research how these rivers are used today. How have social relationships to rivers changed over time? How do rivers affect local communities?

Now consider the environmental impacts of clean waterways. Study a specific pollutant or issue disturbing a river near you. What is currently impacting waterways in your area? What are the potential consequences of these pollutants or activities? Write a persuasive essay that argues for preserving rivers and waterways near you. Cite examples from your research to support your argument.

Standards Connections

The content in this resource has been designed to align with Missouri and Illinois state learning standards and competencies across a variety of grade levels. For each section, we have highlighted a selection of social studies and visual arts standards that have strong connections to the content and activities presented. There are a number of other standards and content areas, such as English language arts, that may also connect with these resource materials. Select the links below for access to key standards and related resources.

-

Missouri Learning Standards

Visual arts

VA:RE.7B.6 Analyze ways that visual components and cultural associations suggested by images influence ideas, emotions, and actions.

VA:Cn11A.5 Identify how art is used to inform or change the beliefs, values, or behaviors of an individual or a society.

VA:Re7B.4 Analyze components in visual imagery that convey messages.Social studies

6-8.AH.4.CC.C Analyze material culture to explain a people’s perspective and use of place.

3.PC.1.D.a Explain how the state of Missouri relies on responsible citizen participation, and draw implications for how people should participate.

5.PC.1.D.a Analyze ways in which citizens have effectively voiced opinions, monitored government, and brought about change, both past and present. -

Illinois Learning Standards

Visual arts

VA:Cn11.1.5 Identify how art is used to inform or change the beliefs, values, or behaviors of an individual or a society.

VA:Cn11.1.8 Distinguish different ways art is used to represent, establish, reinforce, and reflect group identity.

VA:Re7.2.4 a. Analyze components in visual imagery that convey messages.Social studies

SS.CV.1.1 Explain how all people, not just official leaders, play important roles in a community.

SS.CV.4.3 Describe how people have tried to improve their communities over time.

SS.H.2.6-8.MdC Analyze multiple factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

SS.IS.8.6-8.MdAssess individual and collective capacities to take action to address problems and identify potential outcomes.English language arts

Illinois learning standards and instruction

Additional Resources

-

Image Credits

Images in Order of Appearance

George Caleb Bingham, American, 1811–1879; Raftsmen Playing Cards, 1847; oil on canvas; 28 1/16 x 38 1/16 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Ezra H. Linley by exchange 50:1934

John Rogers, American, 1829–1904; The Slave Auction, 1859; painted plaster; 13 1/4 x 9 inches; Albany Institute of History and Art, gift of Mrs. Ledyard Cogswell Jr. from the Benjamin Walworth Arnold Collection 2021.205

Ken Light, American, born 1951; Race Wall, St. Louis, Missouri, 1971, printed 1999; gelatin silver print; image: 12 1/2 x 18 3/4 inches, sheet: 16 x 20 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of August A. Busch Jr., by exchange 39:2021; © Ken Light

Damon Davis, American, born 1985; published by Wildwood Press, St. Louis, Missouri; All Hands on Deck #5, 2015; lithograph; sheet (irregular): 32 x 50 13/16 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, The Sidney S. and Sadie Cohen Print Purchase Fund 9:2016.5; © Damon Davis

Damon Davis and All Hands on Deck project in Ferguson, Missouri, 2014; photograph by Flannery Miller; © Flannery Miller

Emmet Gowin, American, born 1941; The Abandoned and Condemned Village of Times Beach, Missouri, 1989; gelatin silver print; image: 9 5/8 x 9 3/4 inches, sheet: 11 x 14 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of Emmet and Edith Gowin in honor of Eric Lutz 26:2021; © Emmet Gowin

Sam Fentress, American, born 1955; Times Beach, Missouri, 1986, printed 2020; gelatin silver print; image: 7 7/8 x 11 3/8 inches, sheet: 11 x 14 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of Sam and Betsy Fentress 59:2021; photo © Sam Fentress

Jennifer Colten, American, born 1962; Mound 7158, from the project Significant and Insignificant Mounds, 2017; archival pigment print; 26 1/2 x 40 inches; sheet: 30 1/2 x 44 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum 2021.100; Courtesy of the artist; © Jennifer Colten

Jennifer Colten, American, born 1962; Mound 2484, from the project Significant and Insignificant Mounds, 2017; archival pigment print; 26 1/2 x 40 inches; sheet: 30 1/2 x 44 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum 2021.101; Courtesy of the artist; © Jennifer Colten

Jennifer Colten, American, born 1962; Mound 7040, from the project Significant and Insignificant Mounds, 2017; archival pigment print; 26 1/2 x 40 inches; sheet: 30 1/2 x 44 inches; Saint Louis Art Museum 2021.99; Courtesy of the artist; © Jennifer Colten